| Home | Sources Directory | News Releases | Calendar | Articles | | Contact | |

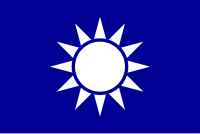

Kuomintang

|

|

This section may stray from the topic of the article into the topic of another article, History of the Kuomintang. Please help improve this section or discuss this issue on the talk page. |

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2009) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Kuomintang of China[4] (English pronunciation: /ˌkwoÊŠmÉ�nˈtÉ�ːÅ�/ or /-ˈtæÅ�/)[5] (KMT); (Hanyu Pinyin: GuómíndçŽng, GMD), translated as the Chinese Nationalist Party or Chinese National People's Party,[6] is a centre-right, Revolutionary, conservative political party of the Republic of China (Taiwan). It can be seen romanized as Guomindang (according to the Pinyin transcription system) in some contexts. It is the founding and currently the ruling political party of the ROC. The headquarters of the KMT are located in Taipei, Taiwan and it is currently the majority party in terms of seats in the Legislative Yuan, and the oldest political party in the Republic of China. The KMT is a member of the International Democrat Union. Current president Ma Ying-jeou is the seventh KMT member to hold the office of the presidency.

Together with the People First Party and Chinese New Party, the KMT forms what is known as the Taiwanese Pan-Blue coalition, which supports eventual unification with the mainland. However, the KMT has been forced to moderate their stance by advocating political and legal status quo of modern Taiwan. The KMT accepts a "One China Principle" - it officially considers that there is only one China and that the Republic of China (not the People's Republic of China) is its legitimate government. However, since 2008, in order to ease tensions with the People's Republic of China, the KMT endorses the "three noes" policy as defined by Ma Ying-jeou - no unification, no independence and no use of force.[7]

The KMT was founded by Song Jiaoren and Sun Yat-sen shortly after the Xinhai Revolution. Later led by Chiang Kai-shek, it ruled much of China from 1928 until its retreat to Taiwan in 1949 after being defeated by the Communist Party of China (CPC) during the Chinese Civil War. There, the KMT controlled the government under a single party state until reforms in the late 1970s through the 1990s loosened its grip on power.

Contents |

[edit] Support

Support for the Kuomintang in the Republic of China encompasses a wide range of groups. Kuomintang support tends to be higher in northern Taiwan and in urban areas, where it draws its backing from small to medium and self-employed business owners, who make up the majority of commercial interests in Taiwan. Big businesses are also likely to support the KMT because of its policy of maintaining commercial links with mainland China.

The KMT also has strong support in the labor sector because of the many labor benefits and insurance implemented while the KMT was in power.[citation needed] The KMT traditionally has strong cooperation with labor unions, teachers, and government workers.[citation needed] Among the ethnic groups in Taiwan, the KMT has solid support among mainlanders and their descendants for ideological reasons and among Taiwanese aboriginals.

Opponents of the KMT include strong supporters of Taiwan independence, and rural residents particularly in southern Taiwan, though supporters of unification include Hoklo and supporters of independence include mainlanders.[citation needed] There is opposition due to an image of KMT both as a mainlanders' and a Chinese nationalist party out of touch with local values.

[edit] History

[edit] Early years, Sun Yat-sen era

The Kuomintang traces its ideological and organizational roots to the work of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, a proponent of Chinese nationalism, who founded Revive China Society in Honolulu, Hawaii in 1894.[8] In 1905, Sun joined forces with other anti-monarchist societies in Tokyo to form the Tongmenghui or the Revolutionary Alliance, a group committed to the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty and the establishment of a republican government.

The group planned and supported the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 and the founding of the Republic of China on January 1, 1912. However, Sun did not have military power and ceded the provisional presidency of the republic to strongman Yuan Shikai, who arranged for the abdication of the Last Emperor on February 12.

On August 25, 1912, the Kuomintang was established at the Huguang Guild Hall in Beijing, where the Revolutionary Alliance and several smaller pro-revolution parties merged to contest the first national elections.[9] Sun, the then Premier of the ROC, was chosen as the party chairman with Huang Xing as his deputy.

The most influential member of the party was the third ranking Song Jiaoren, who mobilized mass support from gentry and merchants for the KMT on a democratic socialist platform in favor of a constitutional parliamentary democracy. The party was opposed to constitutional monarchists and sought to check the power of Yuan. The Kuomintang won an overwhelming majority of the first National Assembly in December 1912.

But Yuan soon began to ignore the parliament in making presidential decisions and had parliamentary leader Song Jiaoren assassinated in Shanghai in 1913. Members of the KMT led by Sun Yat-sen staged the Second Revolution in July 1913, a poorly planned and ill-supported armed rising to overthrow Yuan, and failed. Yuan dissolved the KMT in November (whose members had largely fled into exile in Japan) and dismissed the parliament early in 1914.

Yuan Shikai proclaimed himself emperor in December 1915. While exiled in Japan in 1914, Sun established the Chinese Revolutionary Party, but many of his old revolutionary comrades, including Huang Xing, Wang Jingwei, Hu Hanmin and Chen Jiongming, refused to join him or support his efforts in inciting armed uprising against Yuan Shikai. In order to join the Chinese Revolutionary Party, members must take an oath of personal loyalty to Sun, which many old revolutionaries regarded as undemocratic and contrary to the spirit of the revolution.

Thus, many old revolutionaries did not join Sun's new organisation, and he was largely sidelined within the Republican movement during this period. Sun returned to China in 1917 to establish a rival government at Guangzhou, but was soon forced out of office and exiled to Shanghai. There, with renewed support, he resurrected the KMT on October 10, 1919, but under the name of the Chinese Kuomintang, as the old party had simply been called the Kuomintang. In 1920, Sun and the KMT were restored in Guangdong.

In 1923, the KMT and its government accepted aid from the Soviet Union after being denied recognition by the western powers. Soviet advisers ' the most prominent of whom was Mikhail Borodin, an agent of the Comintern ' began to arrive in China in 1923 to aid in the reorganization and consolidation of the KMT along the lines of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, establishing a Leninist party structure that lasted into the 1990s. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was under Comintern instructions to cooperate with the KMT, and its members were encouraged to join while maintaining their separate party identities, forming the First United Front between the two parties.

Soviet advisers also helped the Nationalists set up a political institute to train propagandists in mass mobilization techniques, and in 1923 Chiang Kai-shek, one of Sun's lieutenants from the Tongmenghui days, was sent to Moscow for several months' military and political study. At the first party congress in 1924, which included non-KMT delegates such as members of the CCP, they adopted Sun's political theory, which included the Three Principles of the People - nationalism, democracy, and people's livelihood.

[edit] Chiang Kai-shek assumes leadership

When Sun Yat-sen died in 1925, the political leadership of the Nationalist Party fell to Wang Jingwei and Hu Hanmin, respectively the left wing and right wing leaders of the Kuomintang. The real power, however, lay with Chiang Kai-shek , also known as Jiang Jieshi, who, as superintendent of the Whampoa Military Academy, was in near complete control of the military.

With this military power, the Kuomintang confirmed their power on Guangzhou, Guangdong (the province containing Guangzhou) and Guangxi (the province west of Guangdong). The Nationalists now had a rival government in direct opposition to the warlord government based in the northern city of Beijing.[10]

Unlike Sun Yat-sen, whom he admired greatly, Chiang Kai-shek, who assumed leadership of the Kuomintang in 1926, had little contact or knowledge of the West. Sun Yat-sen had forged all his political, economic, and revolutionary ideas primarily from Western materials that he had learned in Hawaii and later in Europe. Chiang Kai-shek, however, knew almost nothing about the West; he was firmly rooted in his Chinese identity and was steeped in Chinese culture. As his life progressed, he became more militantly attached to Chinese culture and traditions. His few trips to the West confirmed his pro-Chinese outlook and he studied the Chinese classics and Chinese histories assiduously.[10]

Of the three Principles of the People of Sun Yat-sen, then, the principle he most ardently and passionately adhered to was the principle of nationalism. Chiang was also particularly committed to Sun's idea of "political tutelage"; using this ideology, Chiang built himself into the dictator of the Republic of China, both in the Chinese Mainland, and when the national government was relocated to Taiwan.[10]

Following the death of Sun Yat-sen, General Chiang Kai-shek emerged as the KMT leader and launched the Northern Expedition to defeat the northern warlords and unite China under the party. With their power confirmed in the southeast, the Nationalist government appointed Chiang Kai-shek commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army, and the Northern Expedition to suppress the warlords began. Chiang had to defeat three separate warlords and two independent armies. Chiang, with Soviet supplies, conquered the southern half of China in nine months.

A split, however, erupted between the Chinese Communist Party and the Nationalist Party; this split threatened the Northern Expedition. Joseph Stalin, the leader of the Soviet Union, however, healed the split by ordering the Chinese Communists to obey the Kuomintang leadership in everything. Once this split had been healed, Chiang Kai-shek resumed his Northern Expedition and, with the help of Communist strikes, managed to take Shanghai. There he began to eliminate the Communists in what is today known as the Shanghai massacre of 1927 and the Nationalist government, which had moved to Wuhan, dismissed him. Unfazed, Chiang set up his own alternative government in Nanjing. When the Wuhan government collapsed in February 1928, Chiang Kai-shek was the only Nationalist government still standing.[10]

When Kuomintang forces took Beijing, as the city was the de jure internationally recognized capital, though previously controlled by the feuding warlords, this event allowed the Kuomintang to receive widespread diplomatic recognition in the same year. The capital was moved from Beijing to Nanjing, the original capital of the Ming Dynasty, and thus a symbolic purge of the final Qing elements. This period of KMT rule in China between 1927 and 1937 became and is still known as the Nanjing decade.

Muslim Generals in Gansu waged war against the Guominjun in favor of the Kuomintang during the Kuomintang Jihad in Gansu (1927-1930).

In sum, the KMT began as a heterogeneous group advocating American-inspired federalism and provincial independence. However, after its reorganization along Soviet lines, the party aimed to establish a centralized one party state with one ideology - Three Principles of the People. This was even more evident following Sun's elevation into a cult figure after his death. The control by one single party began the period of "political tutelage," whereby the party was to control the government while instructing the people on how to participate in a democratic system.

The Kuomintang had many Muslim members who used the secular, nationalist ideology of the party to rise up higher in Chinese society.[11] An example of this is after the Northern Expedition, Qinghai and Ningxia provinces were created out of Gansu province, and three Muslim Ma Clique Generals, Ma Qi, Ma Hongkui, and Ma Hongbin were appointed as their military governors for their assistance and their joining the KMT. Bai Chongxi, and Kuomintang member became the Minister of National Defences, the highest position a Muslim had reached in the Chinese government. The Kuomintang sponsored and sent Chinese Muslim students like Muhammad Ma Jian and Wang Jingzhai to study at Al Azhar in Egypt. Ma Fuxiang, a Muslim army General, joined the Kuomintang and filled many important positions as he preached Chinese unity. Ma Hongkui worked with an Imam, Hu Songshan, who ordered all Muslim Imams in Ningxia to preach Chinese nationalism at the mosque and ordered all Muslims to salute the National Flag and pray for the Kuomintang government. Many Muslim generals like Ma Chengxiang and Ma Hushan were hard liner Kuomintang members. The Ma Bufang Mansion, owned by the Muslim General Ma Bufang has numerous portraits of the Kuomintang founder Dr. Sun Yatsen and Blue Sky with a White Sun flags. Muslim Generals like Ma Zhongying used KMT banners and flags for their armies and wore KMT armbands.[12]

After several military campaigns and with the help of German military advisors (German planned fifth "extermination campaign"), the Communists were forced to withdraw from their bases in southern and central China into the mountains in a massive military retreat known famously as the Long March, an undertaking which would eventually increase their reputation among the peasants. Less than 10% of the army would survive the 10,000 km march to Shaanxi province.

The Kuomintang continued to attack the Communists. This was in line with Chiang's policy of solving internal conflicts (warlords and communists) before fighting external invasions (Japan). However, Zhang Xueliang, who believed that the Japanese invasion constituted the greater prevailing threat, took Chiang hostage during the Xi'an Incident in 1937 and forced Chiang to agree to an alliance with the Communists in the total war against the Japanese.

The Second Sino-Japanese War had officially started, and would last until the Japanese surrender in 1945. However in many situations the alliance was in name only; after a brief period of cooperation, the armies began to fight the Japanese separately, rather than as coordinated allies. Conflicts between KMT and communists were still common during the war, and documented claims abound of Communist attacks upon the KMT forces and vice versa.

In these incidents, it should be noted that The KMT armies typically utilized more traditional tactics while the Communists chose guerilla tactics, leading to KMT claims that the Communists often refused to support the KMT troops, choosing to withdraw and let the KMT troops take the brunt of Japanese attacks. These same guerilla tactics, honed against the Japanese forces, were used to great success later during open civil war, as well as the Allied forces in the Korean War and the U.S. forces in the Vietnam War.

During Chiang's rule, the Kuomintang became rampantly corrupt, where leading officials and military leaders hoarded funding, material and armaments. This was especially the case during the Second Sino-Japanese War, an issue which proved to be a hindrance with US military leaders, where military aid provided by the US was hoarded by various KMT generals. US President Truman wrote that "the Chiangs, the Kungs, and the Soongs (were) all thieves" , having taken $750 million in US aid.[13]

The Kuomintang was also known to have used terror tactics against suspected communists, through the utilization of a secret police force, whom were employed to maintain surveillance on suspected communists and political opponents. In 'The Birth of Communist China', C.P. Fitzgerald describes China under the rule of KMT thus: 'the Chinese people groaned under a regime Fascist in every quality except efficiency.' [14]

Full-scale civil war between the Communists and KMT resumed after the defeat of Japan. The Communist armies, previously a minor faction, grew rapidly in influence and power due to several errors on the KMT's part: first, the KMT reduced troop levels precipitously after the Japanese surrender, leaving large numbers of able-bodied, trained fighting men who became unemployed and disgruntled with the KMT as prime recruits for the Communists.

Second, the KMT government proved thoroughly unable to manage the economy, allowing hyperinflation to result. Among the most despised and ineffective efforts it undertook to contain inflation was the conversion to the gold standard for the national treasury and the Gold Standard Script in August 1948, outlawing private ownership of gold, silver, and foreign exchange, collecting all such precious metals and foreign exchange from the people and issuing the Gold Standard Script in exchange.

The new script became worthless in only ten months and greatly reinforced the nationwide perception of KMT as a corrupt or at best inept entity. Third, Chiang Kai-shek ordered his forces to defend the urbanized cities. This decision gave the Communists a chance to move freely through the countryside. At first, the KMT had the edge with the aid of weapons and ammunition from the United States. However, with the country suffering from hyperinflation, widespread corruption and other economic ills, the KMT continued to lose popular support.

At the same time, the suspension of American aid and tens of thousands of deserted or decommissioned soldiers being recruited to the Communist cause tipped the balance of power quickly to the Communist side, and the overwhelming popular support for the Communists in most of the country made it all but impossible for the KMT forces to carry out successful assaults against the Communists.

By the end of 1949, the Communists controlled almost all of mainland China, as the KMT retreated to Taiwan with a significant amount of China's national treasures and 2 million people, including military forces and refugees. Some party members stayed in the mainland and broke away from the main KMT to found the Revolutionary Committee of the Kuomintang, which still currently exists as one of the eight minor registered parties in the People's Republic of China.

[edit] KMT in Taiwan

In 1895, Taiwan, including the Penghu islands, became a Japanese colony, a concession by the Qing Empire after it lost the First Sino-Japanese War. After Japan's defeat at the end of World War II in 1945, General Order No. 1 instructed Japan, who surrendered to the US, to surrender its troops in Taiwan to the forces of the Republic of China Kuomintang.

Taiwan was placed under the administrative control of the Republic of China by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), and the ROC put Taiwan under military occupation. Tensions between the local Taiwanese and mainlanders from mainland China increased in the intervening years culminating in a flashpoint on February 27, 1947 in Taipei when a dispute between a female cigarette vendor and an anti-smuggling officer triggered civil disorder and protests that would last for days. The uprising turned bloody and was shortly put down by the ROC Army in the 228 Incident. As a result of the 228 Incident in 1947, Taiwanese people endured what is called the "White Terror", a KMT-led political repression.

Following the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) on October 1, 1949, the commanders of the PRC People's Liberation Army believed that Kinmen and Matsu had to be taken before a final assault on Taiwan. KMT fought the Battle of Kuningtou and stopped the invasion. In 1950 Chiang took office in Taipei under the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion. The provision declared martial law in Taiwan and halted some democratic processes, including presidential and parliamentary elections, until the mainland could be recovered from the Communists. KMT estimated it would take 3 years to defeat the Communists. The slogan was "prepare in the first year, start fighting in the second, and conquer in the third year."

However, various factors, including international pressure, are believed to have prevented the KMT from militarily engaging the Communists full-scale. The Kuomintang backed Muslim insurgents formerly belonging to the National Revolutionary Army during the Kuomintang Islamic Insurgency in China (1950'1958). A cold war with a couple of minor military conflicts was resulted in the early years. The various government bodies previously in Nanjing were re-established in Taipei as the KMT-controlled government actively claimed sovereignty over all China. The Republic of China in Taiwan retained China's seat in the United Nations until 1971.

Until the 1970s, KMT successfully pushed ahead with land reforms, developed the economy, implemented a democratic system in a lower level of the government, improved cross-Taiwan Strait relations, and created the Taiwan economic miracle. However KMT controlled the government under a one-party authoritarian state until reforms in the late 1970s through the 1990s. The ROC in Taiwan was once referred to synonymously with the KMT and known simply as "Nationalist China" after its ruling party. In the 1970s, the KMT began to allow for "supplemental elections" in Taiwan to fill the seats of the aging representatives in parliament.

Although opposition parties were not permitted, Tangwai (or, "outside the party") representatives were tolerated. In the 1980s, the KMT focused on transforming the government from a single-party system to a multi-party democracy one and embracing "Taiwanizing". With the founding of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in 1986, the KMT started competing against the DPP in Parliamentary elections.

In 1991, martial law ceased when President Lee Teng-Hui terminated the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion. All parties started to be allowed to compete at all levels of elections, including the presidential election. Lee Teng-hui, the ROC's first democratically elected President and the leader of the KMT during the 1990s, announced his advocacy of "special state-to-state relations" with the PRC. The PRC associated it with Taiwan independence.

The KMT faced a split in 1994 that led to the formation of the Chinese New Party, alleged to be a result of Lee's "corruptive ruling style". The New Party has, since the purging of Lee, largely reintegrated into KMT. A much more serious split in the party occurred as a result of the 2000 Presidential election. Upset at the choice of Lien Chan as the party's presidential nominee, former party Secretary-General James Soong launched an independent bid, which resulted in the expulsion of Soong and his supporters and the formation of the People's First Party (PFP). The KMT candidate placed third behind Soong in the elections. After the election, Lee's strong relationship with the opponent became apparent. In order to prevent defections to the PFP, Lien moved the party away from Lee's pro-independence policies and became more favorable toward Chinese reunification. This shift led to Lee's expulsion from the party and the formation of the Taiwan Solidarity Union.

In 2006 the Kuomintang sold its former headquarters to Evergreen Group for $2.3 billion New Taiwan dollars (96 million United States dollars). The KMT moved into a smaller building on Bade Road.[15]

[edit] Current issues and challenges

As the ruling party on Taiwan, the KMT amassed a vast business empire of banks, investment companies, petrochemical firms, and television and radio stations, thought to have made it the world's richest political party, with assets once estimated to be around US$ 2'10 billion.[16] Although this war chest appeared to help the KMT until the mid-1990s, it later led to accusations of corruption (see Black gold (politics)).

After 2000, the KMT's financial holdings appeared to be more of a liability than a benefit, and the KMT started to divest its assets. However, the transactions were not disclosed and the whereabouts of the money earned from selling assets (if it has gone anywhere) is unknown. There were accusations in the 2004 presidential election that the KMT retained assets that were illegally acquired. Currently, there is a law proposed by the DPP in the Legislative Yuan to recover illegally acquired party assets and return them to the government; however, since the pan-Blue alliance, the KMT and its smaller partner PFP, control the legislature, it is very unlikely to be passed.

The KMT also acknowledged that part of its assets were acquired through extra-legal means and thus promised to "retro-endow" them to the government. However, the quantity of the assets which should be classified as illegal are still under heated debate; Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), in its capacity as ruling party from 2000'2008, claimed that there is much more that the KMT has yet to acknowledge. Also, the KMT actively sold assets under its title in order to quench its recent financial difficulties, which the DPP argues is illegal. Former KMT Chairman Ma Ying-Jeou's position is that the KMT will sell some of its properties at below market rates rather than return them to the government and that the details of these transactions will not be publicly disclosed.

In December 2003, then-KMT chairman (present chairman emeritus) and presidential candidate Lien Chan initiated what appeared to some to be a major shift in the party's position on the linked questions of Chinese reunification and Taiwan independence. Speaking to foreign journalists, Lien said that while the KMT was opposed to "immediate independence," it did not wish to be classed as "pro-reunificationist" either.

At the same time, Wang Jin-pyng, speaker of the Legislative Yuan and the Pan-Blue Coalition's campaign manager in the 2004 presidential election, said that the party no longer opposed Taiwan's "eventual independence." This statement was later clarified as meaning that the KMT opposes any immediate decision on unification and independence and would like to have this issue resolved by future generations. The KMT's position on the cross-strait relationship was redefined as hoping to remain in the current neither-independent-nor-united situation.

In 2005, then-party chairman Lien Chan announced that he was to leave his office. The two leading contenders for the position include Ma Ying-jeou and Wang Jin-pyng. On April 5, 2005, Taipei Mayor Ma Ying-jeou said he wished to lead the opposition Kuomintang with Wang Jin-pyng. On 16 July 2005, Ma was elected as KMT chairman in the first contested leadership in Kuomintang's 93-year history. Some 54 percent of the party's 1.04 million members cast their ballots. Ma Ying-jeou garnered 72.4 percent of vote share, or 375,056 votes, against Wang Jin-pyng's 27.6 percent, or 143,268 votes. After failing to convince Wang to stay on as a vice chairman, Ma named holdovers Wu Po-hsiung (Å��ä��É�„), Chiang Pin-kung (Æ��ä��Å��), and Lin Cheng-chi (Æž�Æ�„Æž�), as well as long-time party administrator and strategist John Kuan (É��ä��), as vice-chairmen; all appointments were approved by a hand count of party delegates.

There has been a recent warming of relations between the pan-blue coalition and the PRC, with prominent members of both the KMT and PFP in active discussions with officials on the Mainland. In February 2004, it appeared that KMT had opened a campaign office for the Lien-Soong ticket in Shanghai targeting Taiwanese businessmen. However, after an adverse reaction in Taiwan, the KMT quickly declared that the office was opened without official knowledge or authorization. In addition, the PRC issued a statement forbidding open campaigning in the Mainland and formally stated that it had no preference as to which candidate won and cared only about the positions of the winning candidate.

On March 28, 2005, thirty members of the Kuomintang (KMT), led by KMT vice chairman Chiang Pin-kung, arrived in mainland China. This marked the first official visit by the KMT to the mainland since it was defeated by communist forces in 1949 (although KMT members including Chiang had made individual visits in the past). The delegates began their itinerary by paying homage to the revolutionary martyrs of the Tenth Uprising at Huanghuagang. They subsequently flew to the former ROC capital of Nanjing to commemorate Sun Yat-sen. During the trip KMT signed a 10-points agreement with the CPC. The opponents regarded this visit as the prelude of the third KMT-CPC cooperation. Weeks afterwards, in May, Chairman Lien Chan visited the mainland and met with Hu Jintao. No agreements were signed because Chen Shui-bian's government threatened to prosecute the KMT delegation for treason and violation of R.O.C. laws prohibiting citizens from collaborating with Communists.

On February 13, 2007, Ma was indicted by the Taiwan High Prosecutors Office on charges of allegedly embezzling approximately NT$11 million (US$339,000), regarding the issue of "special expenses" while he was mayor of Taipei. Shortly after the indictment, he submitted his resignation as chairman of the Kuomintang at the same press conference at which he formally announced his candidacy for President. Ma argued that it was customary for officials to use the special expense fund for personal expenses undertaken in the course of their official duties. In December 2007, Ma was acquitted of all charges and immediately filed suit against the prosecutors who are also appealing the acquittal.

On June 25, 2009, ROC President Ma Ying-jeou expressed his bid for KMT leadership, as he registered as the sole candidate for the election of the KMT chairmanship. The election was scheduled for July 26, where the new chairman would take office on September 12. If his bid succeeds, he would become the leader of the KMT, as well as the head-of-state of the Republic of China; in effect, this would officially allow Ma to be able to meet with People's Republic of China President Hu Jintao (who is also the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China) and other PRC delegates, as he would be able to represent the KMT as leader of a Chinese political party, rather than as head-of-state of a political entity unrecognized by the PRC.[17] On July 26, Ma Ying-jeou won 93.87% of the vote for KMT leadership, becoming the new chairman of the Kuomintang.[18]

Some think-tanks such as the Asian European Council have argued that the current tensions between the US and China over Washington's abrupt decision to sell arms to Taipei[19] might trigger a news arms race in Asia fueled essentially by domestic ideological motives, a situation reminiscent in many ways of the McCarthy era[20] when US militarists were overtly favorable to the most right-wing, irredentist elements within the KMT leadership.

[edit] Elections and results

The KMT won a landslide victory in the Republic of China Presidential Election on March 22, 2008. The KMT fielded former Taipei mayor and former KMT chairman Ma Ying-jeou to run against the DPP's Frank Hsieh. Ma won by a large margin of 17% against Hsieh. Ma took office on May 20, 2008 and ended 8 years of the DPP presidency. The KMT also won a landslide victory in the 2008 legislative elections, winning 81 of 113 seats, or 71.7% of seats in the Legislative Yuan. These two elections gave the KMT firm control of both the executive and legislative yuans.

Prior to this, the party's voters had defected to both the PFP and TSU, and the KMT did poorly in the December 2001 legislative elections and lost its position as the largest party in the Legislative Yuan. However, the party did well in the 2002 local government mayoral and council election with Ma Ying-jeou, its candidate for Taipei mayor, winning reelection by a landslide and its candidate for Kaohsiung mayor narrowly losing but doing surprisingly well. Since 2002, the KMT and PFP have coordinated electoral strategies. In 2004, the KMT and PFP ran a joint presidential ticket, with Lien running for president and Soong running for vice-president.

The loss of the presidential election of 2004 to DPP President Chen Shui-bian by merely over 30,000 votes was a bitter disappointment to party members, leading to large scale rallies for several weeks protesting alleged electoral fraud and the "odd circumstances" of the shooting of President Chen. However, the fortunes of the party were greatly improved when the KMT did well in the legislative elections held in December 2004 by maintaining its support in southern Taiwan achieving a majority for the pan-blue coalition.

Soon after the election, there appeared to be a falling out with the KMT's junior partner the People's First Party and talk of a merger seemed to have ended. This split appeared to widen in early 2005, as the leader of the PFP, James Soong appeared to be reconciling with President Chen Shui-Bian and the Democratic Progressive Party. Many PFP members including legislators and municipal leaders have defected to the KMT, and the PFP is seen as a fading party.

The KMT won a decisive victory in the 3-in-1 local elections of December 2005, replacing the DPP as the largest party at the local level. This was seen as a major victory for the party ahead of legislative elections in 2007. There were elections for the two municipalities of the ROC, Taipei and Kaohsiung on December 2006. The KMT won a clear victory in Taipei, but lost to the DPP in the southern city of Kaohsiung by the slim margin of 1,100 votes.

After 8 years of the KMT legislative majority sharing rule with a DPP president, the KMT regained the presidency by winning the 2008 Presidential Election. The citizens of the ROC elected Presidential candidate Ma Ying Jeou and Vice-Presidential candidate Vincent Siew. This followed an earlier election in January of the Legislative Yuan in which the KMT increased their control of the legislature by winning 3 quarters of the total seats.

[edit] Organization

[edit] Leadership history

[edit] List of leaders of the Kuomintang (1912'1914)

President:

- Song Jiaoren (1912'1913)

Premier:

- Sun Yat-sen (1913'1914)

[edit] List of leaders of the Kuomintang of China (1919'present)

Premier:

- Sun Yat-sen (1919'1925)

- Zhang Renjie (1925'1926)

Chairman of Central Executive Committee:

- Hu Hanmin (1927'1931)

- Wang Jingwei (1931'1933)

- Chiang Kai-shek (1933'1938) (self-proclaimed)

Director-General:

- Chiang Kai-shek (1926'1927)

Vacancy (1927'1935) - Hu Hanmin (1935'1936)

Vacancy (1936'1938) - Chiang Kai-shek (1938'1975)

Chairman:

- Chiang Ching-kuo (1975'1988)

- Lee Teng-hui (1988-2000)

- Lien Chan (2000-2005)

- Ma Ying-jeou (2005-2007)

- Wu Po-hsiung (2007) (acting)

- Chiang Pin-kung (2007) (acting)

- Wu Po-hsiung (April 2007'September 12, 2009)

- Ma Ying-jeou (September 12, 2009-)

[edit] Current vice chairpersons

- Chan Chuen-pao (������)

- Lin Fong-cheng (ƞ�����)

- Chiang Pin-kung (�����)

- Chiang Hsiao-yen (����Ś�)

- Tseng Yong-Chuan (Æ��Æ��Æ�Š)

- Huang Ming-Hui (ɻ�����)

[edit] List of Secretaries-General of the Kuomintang of China

Secretaries-General of the Central Executive Committee:

- Yeh Ch'u-ts'ang (È��Æ�šÅ��) (1926'1927)

- Post abolished (1927'1929)

- Chen Li-fu (É��ç«�Å�«) (1929'1931)

- Ting Wei-feng (�����) (1931)

- Yeh Ch'u-ts'ang (1931'1938)

- Chu Chia-hua (Æ��Å��É�Š) (1938'1939)

- Yeh Ch'u-ts'ang (1939'1941)

- Wu Tieh-cheng (Å��É��Å�Ž) (1941'1948)

- Cheng Yen-feng (É„�Å��Æ�») (1948'1950)

Secretaries-General of the Central Reform Committee:

- Chang Chi-yun (������) (1950'1952)

Secretaries-General of the Central Committee:

- Chang Chi-yun (1952'1954)

- Chang Li-sheng (��Ŏ��) (1954'1959)

- Tang Tsung (���) (1959'1964)

- Ku Feng-hsiang (�����) (1964'1968)

- Chang Pao-shu (������) (1968'1979)

- Chiang Yen-si (È��Å��Å�«) (1979'1985)

- Ma Su-lei (�����) (1985'1987)

- Lee Huan (Æ�Žç��) (1987'1989)

- James Soong (Å��Æ�šç��) (1989'1993)

- Hsu Shui-teh (������) (1993'1996)

- Wu Po-hsiung (Å��ä��É�„) (1996'1998)

- Chang Hsiao-yen (���Ś�) (1998'1999)

- Huang Kun-fei (ɻ�����) (1999'2000)

- Lin Fong-cheng (ƞ�����) (2000'2005)

- Chan Chuen-pao (������) (2005'2007)(2009)

- Wu Den-yih (�����) (2007'2009)

- King Pu-tsung (������) (2009'present)

[edit] Party organization and structure[21]

- National Congress

- Party Chairman

- Vice-Chairmen

- Central Committee

- Central Steering Committee for Women

- Central Standing Committee

- Secretary-General

- Deputy Secretaries-General

- Party Chairman

-

- Executive Director

-

-

- Policy Committee

- Policy Coordination Department

- Policy Research Department

- Mainland Affairs Department

- Policy Committee

-

-

-

- National Development Institute

- Administrative Division

- Research Division

- Education and Counselling Division

- National Development Institute

-

-

-

- Party Disciplinary Committee

- Evaluation and Control Office

- Audit Office

- Party Disciplinary Committee

-

-

-

- Culture and Communications Committee

- Cultural Department

- Communications Department

- KMT Party History Institute

- Culture and Communications Committee

-

-

-

- Administration Committee

- Personnel Office

- General Office

- Finance Office

- Accounting Office

- Information Center

- Administration Committee

-

-

-

- Organizational Development Committee

- Organization and Operations Department

- Elections Mobilization Department

- Community Volunteers Department

- Overseas Department

- Youth Department

- Women's Department

- Organizational Development Committee

-

[edit] Ideology

[edit] Chinese Nationalism

The Kuomintang was a nationalist revolutionary party, which had been supported by the Soviet Union. It was organized on Leninism.[22]

The Kuomintang had several influences left upon its ideology by revolutionary thinking. The Kuomintang, and Chiang Kaishek used the words feudal and counterrevolutionary as synonyms for evil, and backwardness, and proudly proclaimed themselves to be revolutionary.[23] Chiang called the warlords feudalists, and called for feudalism and counterrevolutionaries to be stamped out by the Kuomintang.[24][25][26][27] Chiang showed extreme rage when he was called a warlord, because of its negative, feudal connotations.[28]

Chiang Kaishek , the head of the Kuomintang, warned the Soviet Union and other foreign countries about interfering in Chinese affairs. He was personally angry at the way China was treated by foreigners, mainly by the Soviet Union, Britain, and the United States.[25][29] He and his New Life Movement called for the crushing of Soviet, Western, American and other foreign influences in China. Chen Lifu, a CC Clique member in the KMT, said "Communism originated from Soviet imperialism, which has encroached on our country." It was also noted that "the white bear of the North Pole is known for its viciousness and cruelty."[30]

The Kuomintang was anti feudal, using feudal as a negative connotation to refer to backward ways and anti revolutionary ideas.[31] The Blue Shirts Society, a fascist paramilitary organization within the Kuomintang modeled after Mussolini's blackshirts, was anti foreign and anti communist, and stated that its agenda was to expel foreign (Japanese and Western) Imperialists from China, crush communism, and eliminate feudalism.[32] In addition to being anti Communist, some Kuomintang members, like Chiang Kaishek's right hand man Dai Li were anti American, and they wanted to expel American influence.[33]

Kuomintang leaders across China adopted nationalist rhetoric. The Chinese Muslim General Ma Bufang of Qinghai presented himself as a Chinese nationalist to the people of China, fighting against British Imperialism, to deflect criticism by opponents that his government was feudal and oppressed minorities like Tibetans and Buddhist Mongols. He used the Chinese nationalist card to his advantage to keep himself in power.[34][35] The Kuomintang party was officially anti feudal, and the Kuomintang itself claimed to be a revolutionary party of the people, so being accused of feudalism was a serious insult. Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Kuomintang, spoke out publicly against feudalism and feudal warlords.[26] Ma Bufang was forced to defend himself against the accusations, and stated to the news media that his army was a part of "National army, people's power".[36]

[edit] Anti-Imperialism, Anti-Religion, and Anti-Foreignism

During the Northern Expedition, the Kuomintang incited anti-foreign, anti-western sentiment. Portraits of Sun Yatsen replaced the crucifix in several churches, KMT posters proclaimed- "Jesus Christ is dead. Why not worship something alive such as Nationalism?". Foreign missionaries were attacked and anti foreign riots broke out.[37]

The Kuomintang branch in Guangxi province, led by the New Guangxi Clique implemented anti-imperialist, anti-religious, and foreign policies.

During the Northern Expedition, in 1926 in Guangxi, Muslim General Bai Chongxi led his troops in destroying Buddhist temples and smashing idols, turning the temples into schools and Kuomintang party headquarters.[38] It was reported that almost all of Buddhist monasteries in Guangxi were destroyed by Bai in this manner. The monks were removed.[39] Bai led a wave of anti foreignism in Guangxi, attacking American, European, and other foreigners and missionaries, and generally making the province unsafe for foreigners. Westerners fled from the province, and some Chinese Christians were also attacked as imperialist agents.[40]

The three goals of his movement were anti-foreigism, anti-imperialism, and anti-religion. Bai led the anti-religious movement, against superstition. Muslims do not believe in superstition (see Shirk (Islam)) and his religion may have influenced Bai to take action against the Idols in the temples and the superstitious practices rampant in China. Huang Shaoxiong, also a Kuomintang member of the New Guangxi Clique, supported Bai's campaign, and Huang was not a Muslim, the anti religious campaign was agreed upon by all Guangxi Kuomintang members.[41]

As a Kuomintang member, Bai and the other Guangxi clique members allowed the Communists to continue attacking foreigners and smash idols, since they shared the goal of expelling the foreign powers from China, but they stopped Communists from initiating social change.[42]

General Bai also wanted to aggressively expel foreign powers from other areas of China. Bai gave a speech in which he said that the minorities of china were suffering under foreign oppression. He cited specific examples, such as the Tibetans under the British, the Manchus under the Japanese, the Mongols under the Outer Mongolian People's Republic, and the Uyghurs of Xinjiang under the Soviet Union. Bai called upon China to assist them in expelling the foreigners from those lands. He personally wanted to lead an expedition to seize back Xinjiang to bring it under Chinese control, in the style that Zuo Zongtang led during the Dungan revolt.[43]

During the Kuomintang Pacification of Qinghai the Muslim General Ma Bufang destroyed Tibetan Buddhist monasteries with support from the Kuomintang government.[44]

General Ma Bufang, a Sufi, who backed the Yihewani Muslims, and persecuted the Fundamentalist Salafi/Wahhabi Muslim sect. The Yihewani forced the Salafis into hiding. They were not allowed to move or worship openly. The Yihewani had become secular and Chinese nationalist, and they considered the Salafiyya to be "Heterodox" (xie jiao), and people who followed foreigner's teachings (waidao). Only after the Communists took over were the Salafis allowed to come out and worship openly.[45]

[edit] Socialism and Anti-Capitalist Agitation

The Kuomintang had a left wing and a right wing, the left being more radical in its pro Soviet policies, but both wings equally persecuted merchants, accusing them of being counterrevolutionaries and reactionaries. The right wing under Chiang Kaishek prevailed, and continued radical policies against private merchants and industrialists, even as they denounced communism.

One of the Three Principles of the People of the Kuomintang, Mínshä�ng, was defined as socialism as Dr. Sun Yatsen. He defined this principle of saying in his last days "it's socialism and it's communism.". The concept may be understood as social welfare as well. Sun understood it as an industrial economy and equality of land holdings for the Chinese peasant farmers. Here he was influenced by the American thinker Henry George (see Georgism) and German thinker Karl Marx; the land value tax in Taiwan is a legacy thereof. He divided livelihood into four areas: food, clothing, housing, and transportation; and planned out how an ideal (Chinese) government can take care of these for its people.

The Kuomintang was referred to having a socialist ideology. "Equalization of land rights" was a clause included by Dr. Sun in the original Tongmenhui. The Kuomintang's revolutionary ideology in the 1920s incorporated unique Chinese Socialism as part of its ideology.[46][47]

The Soviet Union trained Kuomintang revolutionaries in the Moscow Sun Yat-sen University. In the West and in the Soviet Union, Chiang was known as the "Red General".[48] Movie theaters in the Soviet Union showed newsreels and clips of Chiang, at Moscow Sun Yat-sen University Portraits of Chiang were hung on the walls, and in the Soviet May Day Parades that year, Chiang's portrait was to be carried along with the portraits of Karl Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and other socialist leaders.[49]

The Kuomintang attempted to levy taxes upon merchants in Canton, and the merchants resisted by raising an army, the Merchant's volunteer corps. Dr. Sun initiated this anti merchant policy, and Chiang Kai-shek enforced it, Chiang led his army of Whampoa Military Academy graduates to defeat the merchant's army. Chiang was assisted by Soviet advisors, who supplied him with weapons, while the merchants were supplied with weapons from the Western countries.[50][51]

The Kuomintang were accused of leading a "Red Revolution"in Canton. The merchants were conservative and reactionary, and their Volunteer Corp leader Chen Lianbao was a prominent comprador trader.[52]

The merchants were supported by the foreign, western Imperialists such as the British, who led an international flotilla to support them against Dr. Sun.[53] Chiang seized the western supplied weapons from the merchants, and battled against them. A Kuomintang General executed several merchants, and the Kuomintang formed a Soviet inspired Revolutionary Committee.[54] The British Communist party congragulated Dr. Sun for his war against foreign imperialists and capitalists.[55]

Even after Chiang turned on the Soviet Union and massacred the Communists, he still continued anti merchant activities, and promoting revolutionary thought, accusing the merchants of being reactionaries and counterrevolutionaries.

The United States consulate and other westerners in Shanghai was concerned about the approach of "Red General" Chiang, as his army was seizing control in the Northern Expedition.[56][57]

Chiang also crushed and dominated the merchants of Shanghai in 1927, seizing loans from them, with the threats of death or exile. Rich merchants, industrialists, and entrepreneurs were arrested by Chiang, who accused them of being "counterrevolutionary", and Chiang held them until they gave money to the Kuomintang. Chiang arrests targeted rich millionaiares, accusing them of Communism and Counterrevolutionary activities. Chiang also enforced an anti Japanese boycott, sending his agents to sack the shops of those who sold Japanese made items, fining them. Chiang also disregarded the Internationally protected International Settlement, putting cages on its borders, threatening to have the merchants placed in there. He terrorized the merchant community. The Kuomintang's alliance with the Green Gang allowed it to ignore the borders of the foreign concessions.[58]

In 1948, the Kuomintang again attacked the merchants of Shanghai, Chiang Kaishek sent his son Chiang Ching-kuo to restore economic order. Ching-kuo copied Soviet methods, which he learned during his stay there, to start a social revolution by attacking middle class merchants. He also enforced low prices on all goods to raise support from the Proletariat.[59]

As riots broke out and savings were ruined, bankrupting shopowners, Ching-kuo began to attack the wealthy, seizing assets and placing them under arrest. The son of the gangster Du Yuesheng was arrested by him. Ching-kuo ordered Kuomintang agents ro raid the Yangtze Development Corporation's warehouses, which was privately owned by H.H. Kung and his family. H.H. Kung's wife was Soong Ai-ling, the sister of Soong May-ling who was Ching-kuo's stepmother. H.H. Kung's son David was arrested, the Kung's responded by blackmailing the Chiang's, threatening to release information about them, eventually he was freed after negotiations, and Ching-kuo resigned, ending the terror on the Shanghainese merchants.[60]

The Kuomintang also promotes Government-owned corporations. The Kuomintang founder Sun Yat-sen, was heavily influenced by the economic ideas of Henry George, who believed that the rents extracted from natural monopolies or the usage of land belonged to the public. Dr. Sun argued for Georgism and emphasized the importance of a mixed economy, which he termed "The Principle of Minsheng" in his Three Principles of the People.

"The railroads, public utilities, canals, and forests should be nationalized, and all income from the land and mines should be in the hands of the State. With this money in hand, the State can therefore finance the social welfare programs."[61]

The Kuomintang Muslim Governor of Ningxia, Ma Hongkui promoted state owned monopoly companies. His government had a company, Fu Ning Company, which had a monopoly over commercial and industry in Ningxia.[62] The Kuomintang Muslim Governor of Qinghai, General Ma Bufang was described as a socialist.[63]

Corporations such as CSBC Corporation, Taiwan, CPC Corporation, Taiwan and Aerospace Industrial Development Corporation are owned by the state in the Republic of China.

Marxists also existed in the Kuomintang party. They viewed the Chinese revolution in different terms than the Communists, claiming that China already went past its feudal stage and was already in the capitalist stage.[64]

[edit] Confucianism and Religion in Ideology

The Kuomintang used traditional Chinese religious ceremonies, the souls of Party martyrs who died fighting for the Kuomintang and the revolution and the party founder Dr. Sun Yatsen were sent to heaven according to the Kuomintang party. Chiang Kaishek believed that these martyrs witnessed events on earth from heaven.[65][66][67][68]

When the Northern Expedition was complete, Kuomintang Generals led by Chiang Kaishek paid tribute to Dr. Sun's soul in heaven with a sacrificial ceremony at the Xiangshan Temple in Beijing in July 1928, among the Kuomintang Generals present were the Muslim Generals Bai Chongxi and Ma Fuxiang.[69]

The Kuomintang backed the New Life Movement, which promoted Confucianism, and it was also against westernization.

Imams sponsored by the Kuomintang called for Muslims to go on Jihad to become shaheed (Muslim term for martyr) in battle, where Muslims believed they would go automatically to heaven. Becoming a shaheed in the Jihad for the country was encouraged by the Kuomintang, which was called "glorious death for the state" and a hadith promoting nationalism was spread.[70] A song written by Xue Wenbo at the Muslim Chengda school, which was controlled by the Kuomintang, called for martyrdom in battle for China against Japan.[71]

The Kuomintang also incorporated Confucianism in its jurisprudence. It pardoned Shi Jianqiao for murdering Sun Chuanfang, because she did it in revenge since Sun executed her father Shi Congbin, which was an example of Filial piety to one's parents in Confucianism.[72] The Kuomintang encouraged filial revenge killings and extended pardons to those who performed them.[73]

[edit] Organizations sponsored by the Kuomintang

Ma Fuxiang founded Islamic organizations sponsored by the Kuomintang, including the China Islamic Association (Zhongguo Huijiao Gonghui).[74]

Kuomintang Muslim General Bai Chongxi was Chairman of the Chinese Islamic National Salvation Federation.[75] The Muslim Chengda school and Yuehua publication were supported by the Kuomintang government, and they supported the Kuomintang.[76]

The Chinese Muslim Association was also sponsored by the Kuomintang, and it evacuated from the mainland to Taiwan with the party. The Chinese Muslim Association owns the Taipei Grand Mosque which was built with funds from the Kuomintang.[77]

The Yihewani (Ikhwan al Muslimun a.k.a. Muslim brotherhood) was the predominant Muslim sect backed by the Kuomintang. Other Muslim sects, like the Xidaotang and Sufi brotherhoods like Jahriyya and Khuffiya were also supported by Kuomintang. The Chinese Muslim brotherhood became a Chinese nationalist organization and supported Kuomintang rule, Brotherhood Imams like Hu Songshan ordered Muslims to pray for the Kuomintang government, salute Kuomintang flags during prayer, and listen to nationalist sermons.

[edit] Policy on ethnic minorities

The Kuomintang considers all minorities to be members of the Chinese Nation, Chiang Kai-shek, the Kuomintang party leader, considered all the minority peoples of China, including the Hui, as descedants of Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor and semi mythical founder of the Chinese nation. Chiang considered all the minorities to belong to the Chinese Nation Zhonghua Minzu and he introduced this into Kuomintang ideology, which was propagated into the educational system of the Republic of China, and the Constitution of the ROC considered Chiang's ideology to be true.[78][79][80] In Taiwan, the President performs a ritual honoring Huangdi, while facing west , in the direction of the mainland China.[81]

The Kuomintang kept the Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission for dealing with Mongolian And Tibetan affairs. A Muslim, Ma Fuxiang, was appointed as its Chairman.[82]

Kuomintang was known for sponsoring Muslim students to study abroad at Muslim universities like Al Azhar and it established schools specially for Muslims, Muslim Kuomintang warlords like Ma Fuxiang promoted education for Muslims.[83] The Kuomintang Muslim Warlord Ma Bufang built a girl's school for Muslim girls in Linxia which taught modern secular education.[84]

Tibetans and Mongols refused to allow other ethnic groups like Kazakhs to participate in the Kokonur ceremony in Qinghai, until the Kuomintang Muslim General Ma Bufang forced them to stop the racism and allowed them to particapate.[85]

Chinese Muslims were among the most hardline Kuomintang members. Ma Chengxiang was a Muslim and a Kuomintang member, and refused to surrender to the Communists.[86][87]

The Kuomintang encouraged Muslims and Mongols to overthrow Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan during the Kuomintang Jihad in Gansu (1927'1930).[88]

Masud Sabri, a Uyghur was appointed as Governor of Xinjiang by the Kuomintang, as was the Tatar Burhan Shahidi and the Uyghur Yulbars Khan.[89]

Hui put Kuomintang Blue Sky with a White Sun party symbols on their Halal restaurants and shops. A Christian missionary in 1935 took a picture of a Muslim meat restaurant in Hankow which had Arabic and Chinese lettering indicating that it was Halal (fit for Muslim consumption), and it had two Kuomintang party symbols on it.[90][91]

The Muslim General Ma Bufang also put Kuomintang party symbols on his mansion, the Ma Bufang Mansion along with a portrait of party founder Dr. Sun Yatsen arranged with the Kuomintang Party flag and the Republic of China flag.

General Ma Bufang and other high ranking Muslim Generals attended the Kokonuur Lake Ceremony where the God of the Lake was worshipped, and during the ritual, the Chinese national Anthem was sung, all participants bowed to a Portrait of Kuomintang party founder Dr. Sun Zhongshan, and the God of the Lake was also bowed to, and offerings were given to him by the participants, which included the Muslims.[92] This cult of personality around the Kuomintang party leader and the Kuomintang was standard in all meetings. Sun Yatsen's portrait was bowed to three times by KMT party members.[93] Dr. Sun's portrait was arranged with two flags crossed under, the Kuomintang Party Flag and the Flag of the Republic of China.

The Kuomintang also hosted conferences of important Muslims like Bai Chongxi, Ma Fuxiang, and Ma Liang. Ma Bufang stressed "racial harmony" as a goal when he was Governor of Qinghai.[94]

In 1939 Isa Yusuf Alptekin and Ma Fuliang were sent on a mission by the Kuomintang to the Middle eastern countries such as Egypt, Turkey, and Syria to gain support for the Chinese War against Japan, they also visited Afghanistan in 1940 and contacted Muhammad Amin Bughra, they asked him to come to Chongqing, the capital of the Kuomintang regime. Bughra was arrested by the British in 1942 for spying, and the Kuomintang arranged for Bughra's release. He and Isa Yusuf worked as editors of Kuomintang Muslim publications.[95] Ma Tianying (������) (1900'1982) led the 1939 mission which had 5 other people including Isa and Fuliang.[96]

[edit] Stance on separatism

The Kuomintang is anti separatist, and during its rule on mainland China, it crushed Uyghur and Tibetan separatist uprisings. The Kuomintang claims sovereignty over Mongolia and Tuva as well as the territories of the modern People's Republic and Republic of China.

The Kuomintang Muslim General Ma Bufang waged war on the invading Tibetans during the Sino-Tibetan War with his Muslim army, and he repeatedly crushed Tibetan revolts during bloody battles in Qinghai provinces. Ma Bufang was fully supported by the Kuomintang President of China Chiang Kaishek, who ordered him to prepare his Muslim army to invade Tibet several times and threatened aerial bombardment on the Tibetans. With support from the Kuomintang, Ma Bufang repeatedly attacked the Tibetan area of Golog seven times during the Kuomintang Pacification of Qinghai, eliminating thousands of Tibetans.[44]

General Ma Fuxiang, the chairman of the Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission stated that Mongolia and Tibet were an integral part of the Republic of China.

Our Party [the Guomindang] takes the development of the weak and small and resistance to the strong and violent as our sole and most urgent task. This is even more true for those groups which are not of our kind [Ch. fei wo zulei zhe]. Now the peoples [minzu] of Mongolia and Tibet are closely related to us, and we have great affection for one another: our common existence and common honor already have a history of over a thousand years.... Mongolia and Tibet's life and death are China's life and death. China absolutely cannot cause Mongolia and Tibet to break away from China's territory, and Mongolia and Tibet cannot reject China to become independent. At this time, there is not a single nation on earth execept China that will sincerely develop Mongolia and Tibet."[97]

Under orders from the Kuomintang government of Chiang Kaishek, the Hui General Ma Bufang, Governor of Qinghai (1937'1949), repaired Yushu airport to prevent Tibetan separatists from seeking independence.[98] Ma Bufang also crushed Mongol separatist movements, abducting the Genghis Khan Shrine and attacking Tibetan Buddhist Temples like Labrang, and keeping a tight control over them through the Kokonur God ceremony.[99][100]

During the Kumul Rebellion, the Kuomintang 36th Division (National Revolutionary Army) crushed a separatist Uyghur First East Turkestan Republic, delivering it a fatal blow at the Battle of Kashgar (1934). The Muslim General Ma Hushan pledged alleigance to the Kuomintang and crushed another Uyghur revolt at Charkhlik Revolt.

The Kuomintang also fought against a Soviet and White Russian invasion during the Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang.

During the Ili Rebellion, the Kuomintang fought against Uyghur separatists and the Soviet Union, and against Mongolia.

[edit] See also

|

|

This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Kuomintang |

- History of the Republic of China

- Politics of the Republic of China

- Military of the Republic of China

- Elections in the Republic of China

- Administrative divisions of the Republic of China

- Political status of Taiwan

- Revolutionary Committee of the Kuomintang

- History of the Kuomintang cultural policy

Lists:

[edit] References

- Bergere, Marie-Claire; Janet Lloyd (2000). Sun Yat-sen. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4011-9.

- Roy, Denny (2003). Taiwan: A Political History. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8805-2.

[edit] Notes

- ^ "ä��Å��Å��Æ��É»� É»�Å�� - ä��Å��Å��Æ��É»�Å��ç��È��È�Šç��【Å��É¡�Å��Å�Ž】" (in Traditional Mandarin). ä��Å��Å��Æ��É»�. http://www.kmt.org.tw/hc.aspx?id=34&aid=2774. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ^ Kuomintang Official Website

- ^ http://udn.com/NEWS/NATIONAL/NATS4/4275422.shtml

- ^ http://www.kmt.org.tw/english/page.aspx?type=para&mnum=105

- ^ kuomintang - Definitions from Dictionary.com,(ä��Å��Å��Æ��É»�\ä��Å��Å��Æ��Å�š,pinyin: ZhÅ�ngguó GuómíndçŽng); [kwÉ�Ì�mç�ntÉ�Ì�Å�] in Mandarin

- ^ Derek Benjamin Heater, Our world this century, Oxford University Press, 1987

- ^ http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2008/01/21/2003398185

- ^ See (Chinese) "Major Events in KMT" History Official Site of the KMT last accessed Aug. 30, 2009

- ^ Richard Belsky, "Placing the Hundred Days" in Rebecca E. Karl, Peter Gue Zarrow, Rethinking the 1898 Reform Period: Political and Cultural Change in Late Qing China (Harvard University Asia Center 2002) 153-154; (Chinese) History of the KMT Official Website of the KMT. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Nationalist China". Washington State University. 1996-06-06. http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/MODCHINA/NATIONAL.HTM.

- ^ Wing-tsit Chan (1953). Religious trends in modern China. Columbia University Press. p. 327. http://books.google.com/books?id=BwgWAAAAMAAJ&q=Ma-Hung-kwei&dq=Ma-Hung-kwei&hl=en&ei=lq-VTL2PNoKKlweDsNWmCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CD4Q6AEwBDgU. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 108. ISBN 0521255147. http://books.google.com/books?id=IAs9AAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=warlords+and+muslims&cd=1#v=snippet&q=kuomintang%20%20standard&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Bagby, Wesley Marvin, The Eagle-Dragon Alliance: America's Relations with China in World War II, University of Delaware Press, 1992, pp.65. (ISBN 0874134188)

- ^ C.P. Fitzgerald, The Birth of Communist China, Penguin Books, 1964, pp.106. (ISBN 0140206949 / ISBN 9780140206944)

- ^ Mo, Yan-chih. "KMT headquarters sold for NT$2.3bn." Taipei Times. Thursday March 23, 2006. Page 1. Retrieved on September 29, 2009.

- ^ "Taiwan's Kuomintang On the brink". Economist. 6 December 2001. http://www.economist.com/printedition/displayStory.cfm?Story_ID=898158.

- ^ Taiwan President Ma Ying-jeou registers for KMT leadership race - eTaiwan News

- ^ President Ma elected KMT chairman - CNA ENGLISH NEWS

- ^ AFP (February 2, 2010). "China: US spat over Taiwan could hit co-operation". Agence France Presse. http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5jDzKLVZ7X2dz8yrsshklcJZh38Cg.

- ^ AEC (January 31, 2010). "The New 'China Lobby': Return of the McCarthyite Hard-Right". Asian European Council. http://asianeuropean.org/-McCarthyism_in_Asia_.html.

- ^ http://www.kmt.org.tw/english/page.aspx?type=para&mnum=107

- ^ Jonathan Fenby (2005). Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 504. ISBN 0786714840. http://books.google.com/books?id=GTgEPrlfvG4C&pg=PA337&dq=chiang+portraits+streets&hl=en&ei=UGCaTKLlBsGB8gbyyeBX&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CDsQ6AEwAg#v=snippet&q=leninist%20chiang%20democracy&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jieru Chen, Lloyd E. Eastman (1993). Chiang Kai-shek's secret past: the memoir of his second wife, Chʻen Chieh-ju. Westview Press. p. 19. ISBN 0813318254. http://books.google.com/books?id=IDbvAzXCBH8C&pg=PA19&dq=Dear+Ah+Feng,+the+Chinese+Revolution+is+yet+to+be+completed.+But+I,+a+revolutionary,+feel+down-hearted+and+am+unable+to+devote+my+full+energy+to+our+country.+I+only+want+you+to+promise+me+one+thing+and+then+I+shall+find+strength+again+to+work+hard+for+the+revolution.&hl=en&ei=fTqmTPHmH8L7lwe7lp0Z&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Dear%20Ah%20Feng%2C%20the%20Chinese%20Revolution%20is%20yet%20to%20be%20completed.%20But%20I%2C%20a%20revolutionary%2C%20feel%20down-hearted%20and%20am%20unable%20to%20devote%20my%20full%20energy%20to%20our%20country.%20I%20only%20want%20you%20to%20promise%20me%20one%20thing%20and%20then%20I%20shall%20find%20strength%20again%20to%20work%20hard%20for%20the%20revolution.&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Kai-shek Chiang (1947). Philip Jacob Jaffe. ed. China's destiny & Chinese economic theory. Roy Publishers. p. 225. http://books.google.com/books?id=9e9wAAAAMAAJ&q=Can+we+now+call+these+disguised+warlords+and+new+feudalists+genuine+revolutionaries&dq=Can+we+now+call+these+disguised+warlords+and+new+feudalists+genuine+revolutionaries&hl=en&ei=SjmmTPKiI4Wdlgen2bwY&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CDUQ6AEwAw. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b Simei Qing (2007). From allies to enemies: visions of modernity, identity, and U.S.-China diplomacy, 1945-1960. Harvard University Press. p. 65. ISBN 0674023447. http://books.google.com/books?id=PpproKeP7cwC&pg=PA65&dq=Can+we+now+call+these+disguised+warlords+and+new+feudalists+genuine+revolutionaries&hl=en&ei=SjmmTPKiI4Wdlgen2bwY&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CDAQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=Can%20we%20now%20call%20these%20disguised%20warlords%20and%20new%20feudalists%20genuine%20revolutionaries&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b Kai Shew Chiang Kai Shew (2007). China's Destiny and Chinese Economic Theory. READ BOOKS. p. 225. ISBN 1406758388. http://books.google.com/books?id=bCAjnuU3z-sC&pg=PA225&dq=e+those+disguised+warlords+and+new+feudalists+beneficial+or+harmful+to+the+nation+and+to+the+Revolution%3F+Everyone+severely+condemned+those+that+formerly+controlled+armies+and+the+territory-grabbing+warlords+as+counter-revolutionary.&hl=en&ei=LTqmTOuKCMSqlAePoeAX&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCcQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=e%20those%20disguised%20warlords%20and%20new%20feudalists%20beneficial%20or%20harmful%20to%20the%20nation%20and%20to%20the%20Revolution%3F%20Everyone%20severely%20condemned%20those%20that%20formerly%20controlled%20armies%20and%20the%20territory-grabbing%20warlords%20as%20counter-revolutionary.&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Hongshan Li, Zhaohui Hong (1998). Image, perception, and the making of U.S.-China relations. University Press of America. p. 268. ISBN 0761811583. http://books.google.com/books?id=gnmxDpX7ZlsC&pg=PA268&dq=Can+we+now+call+these+disguised+warlords+and+new+feudalists+genuine+revolutionaries&hl=en&ei=SjmmTPKiI4Wdlgen2bwY&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=Can%20we%20now%20call%20these%20disguised%20warlords%20and%20new%20feudalists%20genuine%20revolutionaries&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jieru Chen, Lloyd E. Eastman (1993). Chiang Kai-shek's secret past: the memoir of his second wife, Chʻen Chieh-ju. Westview Press. p. 226. ISBN 0813318254. http://books.google.com/books?id=IDbvAzXCBH8C&pg=PA226&dq=see+his+face+was+livid+and+his+hands+were+shaking+%E2%80%93+he+ran+amok.+He+swept+things+off+the+table+and+broke+the+furniture+by+smashing+chairs+and+overturning+tables.+Then,+like+a+baby,+he+broke+down+and+wept+bitterly.+All+that+afternoon+and+evening,+he+refused+to&hl=en&ei=lDqmTLbMNYa0lQfd0pUY&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=see%20his%20face%20was%20livid%20and%20his%20hands%20were%20shaking%20%E2%80%93%20he%20ran%20amok.%20He%20swept%20things%20off%20the%20table%20and%20broke%20the%20furniture%20by%20smashing%20chairs%20and%20overturning%20tables.%20Then%2C%20like%20a%20baby%2C%20he%20broke%20down%20and%20wept%20bitterly.%20All%20that%20afternoon%20and%20evening%2C%20he%20refused%20to&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jonathan Fenby (2005). Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 413. ISBN 0786714840. http://books.google.com/books?id=YkREps9oGR4C&dq=generalissimo+and+he+lost&q=chiang+american+motives#v=snippet&q=chiang%20did%20not%20like%20ally%20american%20motives&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Hongshan Li, Zhaohui Hong (1998). Image, perception, and the making of U.S.-China relations. University Press of America. p. 268. ISBN 0761811583. http://books.google.com/books?id=gnmxDpX7ZlsC&pg=PA268&dq=Can+we+now+call+these+disguised+warlords+and+new+feudalists+genuine+revolutionaries&hl=en&ei=SjmmTPKiI4Wdlgen2bwY&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=soviet%20imperialism%20country%20the%20white%20bear%20of%20the%20North&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Edgar Snow (2008). Red Star Over China - The Rise of the Red Army. READ BOOKS. p. 89. ISBN 1443736732. http://books.google.com/books?id=yYUABRj8IDwC&pg=PA89&dq=kuomintang+anti+feudal&hl=en&ei=1DamTObUKIaBlAfLu5gX&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CFcQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=kuomintang%20anti%20feudal&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Frederic E. Wakeman (2003). Spymaster: Dai Li and the Chinese secret service. University of California Press. p. 75. ISBN 0520234073. http://books.google.com/books?id=jYYYQYK6FAYC&pg=PA75&dq=blueshirts+red+bandits+foreign+insults&hl=en&ei=gWmaTKa2L8G88gaF0rSxAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCsQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jonathan Fenby (2005). Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 414. ISBN 0786714840. http://books.google.com/books?id=GTgEPrlfvG4C&dq=chiang+portraits+streets&q=chiang+alientae+stalin#v=snippet&q=dai%20li%20oss%20anti%20american%20influence&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 48. ISBN 0742511448. http://books.google.com/books?id=g3C2B9oXVbQC&dq=ma+bufang+chinese+nationalism&q=patriotism#v=onepage&q=patriotism%20ma%20bufang%20british&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 49. ISBN 0742511448. http://books.google.com/books?id=g3C2B9oXVbQC&dq=ma+bufang+chinese+nationalism&q=patriotism#v=onepage&q=patriotism%20ma%20bufang%20family%20feudalism&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 50. ISBN 0742511448. http://books.google.com/books?id=g3C2B9oXVbQC&pg=PA47&dq=ma+bufang+chinese+nationalism&hl=en&ei=MebJTMDdIoLGlQeZ-rSgAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CEcQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=ma%20bufang%20army%20national%20army%20people's%20power&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jonathan Fenby (2005). Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 126. ISBN 0786714840. http://books.google.com/books?id=YkREps9oGR4C&dq=chiang+kai-shek+democracy&q=emocracy+absolutely+impossible#v=onepage&q=portraits%20crucifixes%20anti&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0521202043. http://books.google.com/books?id=tCA9AAAAIAAJ&dq=accused+chiang+feudal&q=muslim#v=onepage&q=pai%20smashing%20idols%20decapitating%20statues&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Don Alvin Pittman (2001). Toward a modern Chinese Buddhism: Taixu's reforms. University of Hawaii Press. p. 146. ISBN 00824822315. http://books.google.com/books?id=LxDUeWdMubkC&pg=PA146&dq=bai+chongxi+buddhist+temples&hl=en&ei=qvukTJfKO4OB8gb-mamEAg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=bai%20chongxi%20buddhist%20temples&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0521202043. http://books.google.com/books?id=tCA9AAAAIAAJ&dq=accused+chiang+feudal&q=muslim#v=snippet&q=missionary%20crowd&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0521202043. http://books.google.com/books?id=tCA9AAAAIAAJ&dq=accused+chiang+feudal&q=muslim#v=onepage&q=pai's%20as%20a%20moslem%20other%20religions&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 0521202043. http://books.google.com/books?id=tCA9AAAAIAAJ&dq=accused+chiang+feudal&q=muslim#v=onepage&q=provincial%20kuomintang%20iconoclastic%20foreign&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Diana Lary (1974). Region and nation: the Kwangsi clique in Chinese politics, 1925-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 0521202043. http://books.google.com/books?id=tCA9AAAAIAAJ&dq=accused+chiang+feudal&q=muslim#v=onepage&q=pai%20minority%20tibetans%20british%20foreign&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 273. ISBN 0742511448. http://books.google.com/books?id=g3C2B9oXVbQC&dq=ma+bufang+son&q=genocidal#v=snippet&q=ma%20bufang's%20seven%20genocidal%20golog&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ BARRY RUBIN (2000). Guide to Islamist Movements. M.E. Sharpe. p. 800. ISBN 0765617471. http://books.google.com/books?id=wEih57-GWQQC&pg=PA79&dq=ma+bufang+secret+war&hl=en&ei=Lh6YTKKkLYT68AbGy7iKAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCgQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=ma%20bufang%20secret%20war&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Arif Dirlik (2005). The Marxism in the Chinese revolution. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 20. ISBN 0742530698. http://books.google.com/books?id=S-aGLEtx7AYC&pg=PA20&dq=the+program+rested+the+origins+of+the+rather+unique+socialism+of+the+Guomindang+and+of+Sun+Yat-sen&hl=en&ei=IkCpTJDXFsT7lwehtpCPDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=the%20program%20rested%20the%20origins%20of%20the%20rather%20unique%20socialism%20of%20the%20Guomindang%20and%20of%20Sun%20Yat-sen&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Von KleinSmid Institute of International Affairs, University of Southern California. School of Politics and International Relations (1988). Studies in comparative communism, Volume 21. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 134. http://books.google.com/books?id=VHnmAAAAMAAJ&q=the+program+rested+the+origins+of+the+rather+unique+socialism+of+the+Guomindang+and+of+Sun+Yat-sen&dq=the+program+rested+the+origins+of+the+rather+unique+socialism+of+the+Guomindang+and+of+Sun+Yat-sen&hl=en&ei=RkCpTK-OIcT_lge-xYnVDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAQ. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Hannah Pakula (2009). The last empress: Madame Chiang Kai-Shek and the birth of modern China. Simon and Schuster. p. 346. ISBN 1439148937. http://books.google.com/books?id=4ZpVntUTZfkC&pg=PA246&dq=chiang+was+then+known+as+the+red+general+movies&hl=en&ei=TXiaTISmAcT38Abi7fyWAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCwQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=chiang%20was%20then%20known%20as%20the%20red%20general%20movies&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jay Taylor (2000). The Generalissimo's son: Chiang Ching-kuo and the revolutions in China and Taiwan. Harvard University Press. p. 42. ISBN 0674002873. http://books.google.com/books?id=_5R2fnVZXiwC&pg=PA42&dq=chiang+portraits+streets&hl=en&ei=UGCaTKLlBsGB8gbyyeBX&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CFIQ6AEwBg#v=snippet&q=chiang%20portraits%20marx&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Jonathan Fenby (2005). Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 71. ISBN 0786714840. http://books.google.com/books?id=YkREps9oGR4C&dq=chiang+kai-shek+democracy&q=emocracy+absolutely+impossible#v=onepage&q=merchants%20militia&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Hannah Pakula (2009). The last empress: Madame Chiang Kai-Shek and the birth of modern China. Simon and Schuster. p. 128. ISBN 1439148937. http://books.google.com/books?id=4ZpVntUTZfkC&pg=PA39&dq=I+have+often+thought+that+i+am+the+most+clever+woman+that+ever+lived,+and+others+cannot+compare+with+me&cd=1#v=snippet&q=merchants%20levy%20taxes&f=false. Retrieved 2010-06-28.