| Home | Sources Directory | News Releases | Calendar | Articles | | Contact | |

Society of the Mongol Empire

|

|

This article has no lead section, so one should be written. See the lead section guide for more information on writing leads. (March 2010) |

Contents |

[edit] Food in the Mongolian Empire

During the Mongolian Empire there were two different groups of food, 'white foods' and 'brown foods'[1]. 'White foods' were usually dairy products and were the main food source during the summer. The main dairy product that Mongols lived on during the summer was 'airag' or fermented mare's milk which is widely drunk today. The Mongolians rarely drank milk fresh but often used it to create other foods, including cheese and yogurt. 'Brown foods' were usually meat and were the main food source during the winter. Anytime meat was served in the Empire it was usually boiled and served with wild garlic or onions. The Mongols had a unique way of slaughtering their animals to get meat. The animal was laid on its back and restrained. Then the butcher would cut its chest open and rip open the aorta, which would cause deadly internal bleeding. Animals would be slaughtered in this fashion because it would keep all of the blood inside of the carcass. Once all of the internal organs were removed the blood was then drained out and used for sausages.[2]

The Mongols also hunted animals as a food source. Some of these animals included rabbit, deer, wild boar, and even wild rodents such as squirrels and marmots. During the winter the Mongols would also get fish via ice fishing. The Mongols rarely slaughtered animals during the summer but if an animal died of natural causes they made sure to carefully preserve it. This was done by cutting the meat into strips and then letting it dry by the sun and the wind. During the winter sheep were the only domestic animal slaughtered, but horses were occasionally slaughtered for ceremonies.[3]

Meal etiquette existed only during large gatherings and ceremonies. The meal, usually meat, was cut up into small pieces. Guests were served their meat on skewers and the host determined the order of serving. People of different social classes were assigned to different parts of the meat and it was the responsibility of the server or the 'ba'urchis' to know who was in each social class. The meat was eaten with fingers and the grease was wiped on the ground or on clothing. The most commonly imported fare was liquor. Most popular was Chinese rice wine and Turkestani grape wine. Genghis Khan was first presented grape wine in 1204 but he dismissed it as dangerously strong. Drunkenness was common at festivals and gatherings. Singing and dancing were also common after the consumption of alcohol. Due to Turkestani and Middle Eastern influences noodles started to appear in Mongolian food. Spices such as cardamom and other food such as chickpeas and fenugreek seeds also became part of the diet due to these external influences.[4][5]

[edit] Money in the Mongolian Empire

One of the most impressive discoveries that Marco Polo made on his visit to Mongolia is how the empire's monetary system worked. He was not impressed by the silver Akçe that the empire used for a unified currency, or that some realms of the empire still used local currency, but he was most surprised by the fact that in some parts of the empire the people used paper currency.[6]

Marco Polo considered the use of paper currency in the Mongolian Empire one of the marvels of the world. Paper currency wasn't used in all of the empire. The Chinese silver ingot was accepted as universal currency throughout the empire and other local coins were used in the western part of the kingdom. Paper currency was used in what was China before the Mongols conquered it. The Chinese had mastered the technology of printmaking and therefore it was relatively simple for them to print bills. Paper currency was used in China because in 960 A.D. the Song Dynasty started replacing their copper coinage with paper currency. When the Mongols invaded the Song Dynasty they started issuing their own Mongolian bills in 1227. This first attempt by the Mongols did not last long because the paper currency was not unified throughout China and they expired after a couple of years. In 1260 Khubilai Khan created China's first unified paper currency with bills that did not have any expiration date. To validate the currency it was fully exchangeable to silver and gold and was accepted as tax payments. Currency distribution was small at first but the war against the Song in South China and Japan made the distribution of the currency increase by 14 fold. With the defeat of the Song, their bills were taken out of circulation and could be exchanged with the current currency with an extraordinary value of 50 to 1. Being the first government to have any sort of paper currency, foreigners understood nothing about it, and some even considered it a form of magic. Regardless of persistent inflation after 1272 paper currency backed by limited releases of coins remained as the standard means of currency until 1345. Around 1345 rebellions, economic crisis and financial mismanagement of the paper currency destroyed the public's confidence in the bills.[7]

Paper money wasn't extremely easy to adopt because it was a foreign concept in the beginning and it wasn't a precious metal, it was just a piece of paper. To initiate the transition from other forms of compensation to paper currency the government made refusing to accept the bill punishable by death. To avoid devaluation the penalty for forging or counterfeiting was death as well.[8][9]

[edit] Domestic animals in the Mongolian Empire

The five domestic animals most important in the Mongolian Empire were horses (most important), cattle, camels, sheep, and goats. All of these animals were valued for their milk and all of the animals' hides were used for clothing and shelter. Though often considered unattractive by other cultures, Mongolian domestic animals were well adapted to cold weather as well as shortages of food and water. These animals were and still are known to survive under these conditions while animals from other regions perish.

[edit] Horses

Horses were by far the most important animal to the ancient Mongols. Not only were they fairly self sufficient, but they were hardy and fast. Smaller than most, these animals could travel long distances without fatigue. They were also well adapted to the harsh winters and dig through the snow looking for grass to feed off of. Almost every family possessed at least one horse, and in some cases, horses were buried with their owners to serve with them in the next life. Mongolian horses were probably the most important factor of the Mongolian Empire. Without the extremely skilled, not to mention famous, cavalry, the Mongols would not have been able to raid and capture the huge area they did and the Mongols would not be known, even today, as skilled horsemen. It also served as an animal that Mongols could drink blood from, by cutting into vein of a horse and drinking it, especially on harsh, long rides from place to place; and for additional sustenance, horse milk was made into liquor. Also, these horses allowed the Mogols to travel thirteen miles per hour which is great for ancient times.[10].

[edit] Cattle

Cattle were used mainly as beasts of burden but they were also valued for their milk, though not as much so for their meat. They lived on the open range and were fairly easy to maintain. They were released early in the morning to graze without a herder or overseer and wandered back on their own in the afternoon. Though they were a part of the domestic animal population, they were not that common in the early empire. In the early time period, only nine percent of all domestic animals were cattle.[11]

[edit] Camels

Camels, along with cattle, were also used as beasts of burden. As they were domesticated (between 4000-3000 BC), they became one of the most important animals for land based trade in Asia. The reasons for this were that they did not require roads to travel on, they could carry up to 500 pounds of goods and supplies, and they did not require much water for long journeys. Besides being beasts of burden, camels' hair was used as a main fiber in Mongolian textiles.[12]

[edit] Sheep/Goats

Sheep and goats were most valued for their milk, meat, and wool. The wool of sheep in particular was very valuable. The shearing was usually done in the spring before the herds were moved to mountain pastures. Most importantly, it was used for making felt to insulate Mongolian homes, called gers, however it was also used for rugs, saddle blankets, and clothing. Ideal herd numbers were usually about 1000. To reach this quota, groups of people would combine their herds and travel together with their sheep and goats.[13]

[edit] Traditional Mongolian Clothing

During the Mongolian Empire, there was a uniform type of Mongol dress though variations according to wealth, status, and gender did occur. These differences included the design, color, cut, and elaborateness of the outfit. The first layer consisted of a long, ankle length robe called a caftan. Some caftans had a square collar but the majority overlapped in the front to fasten under the arm creating a slanting collar. The skirt of the caftan was sewn on separately, and sometimes ruffles were added depending on the purpose and class of the person wearing it. Men and unmarried women tied their caftans with two belts, one thin, leather one beneath a large, broad sash that covered the stomach. Once a woman became married, she stopped wearing the sash. Instead she wore a very full caftan and some had a short-sleeved jacket that opened in the front. For women of higher rank, the overlapping collar of their caftan was decorated with elaborate brocade and they wore full sleeves and a train that servants had to carry. For both genders, trousers were worn under the caftan probably because of the nomadic traditions of the Mongol people.

The materials used to create caftans varied according to status and wealth. They ranged anywhere from silk, brocade, cotton, and valuable furs for richer groups, to leather, wool, and felt for those less well off. Season also dictated the type of fabric worn, especially for those that could afford it. In the summer, Middle Eastern silk and brocades were favored whereas in the winter furs were used to add additional warmth. During the Mongolian Empire, people did not believe in washing their clothes, or themselves. They refrained from doing this because it was their traditional belief that by washing, they would pollute the water and anger the dragons that controlled the water cycle. Therefore, clothes were often not changed until they fell off or fell apart, except for holidays when specialized robes were worn. Because of this, the smell of the outfit was seen as an important aspect of the wearer. For example, if the Great Khan were to give his previously worn clothing (with his smell on it) to a loyal subject, it would be considered a great honor to have not only the clothing, but the smell as well.

Color was also an important characteristic of clothing because it had important symbolic meaning. During large festivities held by the Khan, he would give his important diplomats special robes to wear with specific colors according to what was being celebrated. These were worn only during the specific festival, and if one was caught wearing it at other times, punishments were extremely severe.

The footwear of the traditional Mongolian Empire consisted mainly of boots or leather sandals made out of cow fur. This footwear was thick and often smelled of cow dung. Both the left foot and the right foot were identical and they were made of leather, cotton, or silk. Many layers were sewn together to create the sole of the boot then separately made uppers were attached. The upper sections of the boots were usually dark in color and the soles were light. Light strips of fabric were sewn over the seams to make them more durable. Boots usually had a pointed or upturned toe but lacked a heel.[14][15][16] [17]

[edit] Tools of Warfare

From 1206 to 1405 the Mongolian Empire displayed their military strength by conquering land between the Yellow Sea and the Eastern European border. This would not have been possible without their specialized horses, bows and arrows, and swords. They conquered numerous neighboring territories, which eventually led to history's largest contiguous land-based empire.

The Mongolian Empire utilized the swiftness and strength of the horses to their advantage. Despite being only 12 to 13 hands high, the Mongols respected these small animals. At a young age, boys trained with the horses by hunting and herding with them. Eventually they became experienced riders, which prepared them for the military life that awaited them when they turned fifteen years old. Once these boys become soldiers, four to seven horses were given to them to alternate between. This large number of horses ensured that some were always rested and ready to fight. Because of this, a soldier had little excuse to fall behind in his tasks. Overall, the Mongol Society adored these animals because of their gentleness and loyalty to its master. Anyone who abused or neglected to feed these horses properly was subjected to punishment by the government.

The Mongol Empire considered horses as an important factor to its success and tailored other weapons to them. The bow and arrow was created to be light enough to attack enemies while on horseback. The Mongols used composite bows made from birch, sinew and the horns of sheep. This made sturdy but light bows. Three types of arrows were created for different purposes. The most common arrow used for warfare was the pointed iron head, which could travel as far as 200 metres. If a soldier wanted to slice the flesh of the opposing member, the v-shaped point was used. In times of war, soldiers would shoot the third form of arrow with holes, used for signalling. By listening to the whistling sounds that were produced by this type of arrow, soldiers were able to march in a required direction.

Soldiers primarily used horses and the bow and arrow in times of war, but the military took extra precautions. They prepared for any close range combat by supplying the soldiers with swords, axes, spears, and forks. Halberds, a pole with a two sided blade, were given to those of wealth and the remaining members of the military carried clubs or maces. Along with these necessities, the military provided their soldiers with leather sacks and files. The leather sacks were used to carry and keep items such as weapons dry also they could be inflated and used as floats during river crossings, while the files were for sharpening the arrows. If any soldier was found missing his weapons, he would be punished. Some punishment would be getting whipped, doing very hard physical activities, or possibly having to leave the army.

Even though the military of the Mongol Empire provided weapons for every soldier, armor was available only to the wealthier soldiers. These individuals wore iron chains or scales, protected their arms and legs with leather strips, wore iron helmets, and used iron shields. The horses of the more well to do were also protected to their knees with iron armor and a head plate. Unfortunately, majority of the soldiers in the Mongol Empire were poor. Therefore, many walked into battle with minimal protection in comparison to the lucky few although all of the soldiers had very little armor compared to the knights in armor of Europe.[18] [19] [20] [21] [22]

[edit] Women of the Mongolian Empire

Compared to other civilizations, Mongolian women had the power to influence society. Even though men were dominant in society, many turned to women in their lives for advice. While developing organizations within the Mongol Empire, Genghis Khan asked for assistance from his mother. He honored the advices women in his life offered. Genghis Khan permitted his wives to sit with him and encouraged them to voice their opinions. Because of their help, Genghis was able to choose his successor.

The Mongols considered marriage as the passage into adulthood. Before marriages could proceed, the bride's family was required to offer 'a dowry of clothing or household ornaments' to the groom's mother. To avoid paying the dowry, families could exchange daughters or the groom could work for his future father-in-law. Once the dowry was settled, the bride's family presented her with an inheritance to the livestock or to the servants. Typically, married women of the Mongol Empire wore headdresses to distinguish themselves from the unmarried women.

Marriages in the Mongol Empire were arranged, but men were permitted to practice polygamy. Since each wife had their own yurt, the husband had the opportunity to choose where he wanted to sleep each night. Visitors to this region found it remarkable that marital complications did not arise. The location of the yurts between the wives differed depending on who married first. The first wife placed her yurt to the east and the other wives placed their yurts to the west. Even though a husband remained attached to his first wife, the women were 'docile, diligent, and lacked jealousy' towards one another.

After the husband has slept with one of his wives, the others congregated to her yurt to share drinks with the couple. The wives of the Mongol Empire were not bothered by the presence of the other women in their household. As a married woman, she displayed her 'maturity and independence from her father' to society. The women devoted their lives to their daily tasks, which included physical work outside the household. Women worked by loading the yurts, herding and milking all the livestock, and making felt for the yurt. Along with these chores, she was expected to cook and sew for her husband, her children, and her elders.

A wife's devotion to her husband continued after his death. Remarriages during the Mongol Empire did not occur often. Instead, her youngest son or her youngest brother took care of her.[19] [20] [21] [23] [24]

Mongol women enjoyed more freedoms than those in their foreign vassal countries. They refused to adopt the Chinese practice of footbinding and wear chadors or burqas. The Mongolian women were allowed to move about more freely in public. Toward end of the Mongol Empire, however, the increasing influence of Neo-Confucianism, Buddhism and Islamicization saw greater limits placed on Mongol women.[25]

[edit] Mongol Dwellings

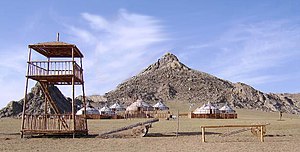

Mongols have been living in virtually the same dwellings since at least the 6th century A.D. These dwellings are called yurts and during the Mongol Empire, they consisted of a round, collapsible wooden frame covered in felt. The roof was formed from about 80 wooden rods attached at one end to the wall frame and at the other to an iron ring in the center, providing a sturdy base for the felt roof. Without the roof in place, this frame would have resembled a large wooden wheel with the wooden spokes converging at the iron ring. The top of the roof was usually about five feet higher than the walls so precipitation would run to the ground. The ring at the peak of the yurt could be left open as a vent for smoke and a window for sunlight, or it could be closed with a piece of felt. Doors were made from a felt flap or, for richer families, out of wood.

The word yurt means 'homeland' in Turkish and it was probably never used to describe the tent. When the dwelling made its way to Mongolia, it adopted the name 'ger' which means 'home' in Mongolian. Yurts were always set up with the door facing the south and tended to have an altar across from the door whether the inhabitant were Buddhist or shamanist. The floors were dirt, but richer families were able to cover the floors with felt rugs. Sometimes beds were used, but most people slept on the floor between hides, around the fire pit that was in the center of the dwelling.

The first known yurt was seen engraved on a bronze bowl that was found in Zagros Mountains of southern Iran, dating back to 600 B.C., but the felt tent probably did not arrive in Mongolia for another thousand years. When the yurt did arrive, however, it quickly came into widespread use because of its ability to act in concert with the nomadic lifestyle of the Mongols. Most of the Mongol people were herders and moved constantly from southern regions in the winter months to the northern steppes in summer as well as moving periodically to fresh pastures. The yurts size and the felt walls made them relatively cool in the summers and warm in the winters allowing the Mongols to live in the same dwelling year-round. Disassembling the yurts only took about an hour, as did putting them back up in a new location. This is why there are still some doubts today about the assumption that the yurts have ever been really put on carts pulled by oxen for transporting them from camp to camp, without disassembling them, or if these carts are just a legend. Some travelers, like Marco Polo, did mention them in their writings: 'They [the Mongols] have circular houses made of wood and covered with felt, which they carry about with them on four wheeled wagons wherever they go. For the framework of rods is so neatly constructed that it is light to carry.' (Polo, 97) Yurts could be heated with cow pies, found in abundance with the traveling herds, so no timber was needed. The felt for the covering was made from wool that was taken from sheep also present in most Mongol's herds. The wooden frame was handed down from one generation to the next and seldom had to be replaced.

Today, yurts follow the same basic design though they are usually covered in canvas, use an iron stove and stovepipe, and use a collapsible lattice work frame for the walls. They are still used in parts of rural China, central Mongolia, and by the Kyrgyz of Kyrgyzstan.[26][27][28][29]

[edit] References

- ^ Charles Bawden. Mongolian-English Dictionary

- ^ Allsen, Thomas T. Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001. 128-129

- ^ Amitai-Preiss, Reuven, and David O. Morgan, eds. The Mongol Empire and Its Legacy. Leiden: Brill, 1999. 200-222

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. "Daily Food in the Mongol Empire." The Encyclopedia of The Mongols and the Mongolian Empire. 1 vols. New York: Facts on File, 2004

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. "Food and Drink." The Encyclopedia of The Mongols and the Mongolian Empire. 1 vols. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

- ^ Allsen, Thomas T. Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001. 177-179.

- ^ Amitai-Preiss, Reuven, and David O. Morgan, eds. The Mongol Empire and Its Legacy. Leiden: Brill, 1999. 200-222.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. "Paper Currency in the Mongol Empire." The Encyclopedia of The Mongols and the Mongolian Empire. 1 vols. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. "Money in the Mongol Empire." The Encyclopedia of The Mongols and the Mongolian Empire. 1 vols. New York: Facts on File, 2004..

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. 'Cattle'. The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. 1 vol. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

- ^ Polo, Marco. The Travels. Ed. Ronald Latham London: Penguin Books, 1598.

- ^ Central Asian Nomads. University of Washington Web Page. 19 Sept. 2006. [depts.washington.edu/silkroad/culture/animals/animals.edu]

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. 'Sheep'. The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. 1 vol. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

- ^ Polo, Marco. The Travels. Ed. Ronald Latham London: Penguin Books, 1598.

- ^ Allsen, Thomas T. Commodity and Trade in the Mongol Empire: A Cultural History of Islamic Textiles. Massachusetts. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. 'Clothing'. The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. 1 vol. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. 'Footwear'. The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. 1 vol. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. 'The Soldiers:Weaponry, Training, Rewards.' The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. 1 vol. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

- ^ a b Howorth, Sir Henry H. History of the Mongols:Part IV. Taipei: Ch'eng Wen Publishing Company, 1970.

- ^ a b Hyer, Paul, and Sechin Jagchid. Mongolia's Culture and Society. Boulder: Westview Press, 1979.

- ^ a b Lamb, Harold. The March of the Barbarians. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc, 1940.

- ^ Phillips, E.D. Ancient Peoples and Placed: The Mongols. 64 vols. London: Thames and Hudson, 1969.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. 'The Mongol Empire.' The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. 1 vol. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

- ^ Polo, Marco. The Travels. Ed. Ronald Latham London: Penguin Books, 1958

- ^ Peggy Martin-AP World History, p.133

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P. Encyclopidia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York, NY: Facts on File, 2004.

- ^ Howorth, Henry H. History of the Mongols. Vol. 4. New York, NY: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1927.

- ^ Polo, Marco. The Travels. Trans. Ronald Latham. England: Penguin Books, 1958.

- ^ "UlaanTaij - Bringing Mongolia to the World." UlaanTaij. 19 Sept. 2006

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

SOURCES.COM is an online portal and directory for journalists, news media, researchers and anyone seeking experts, spokespersons, and reliable information resources. Use SOURCES.COM to find experts, media contacts, news releases, background information, scientists, officials, speakers, newsmakers, spokespeople, talk show guests, story ideas, research studies, databases, universities, associations and NGOs, businesses, government spokespeople. Indexing and search applications by Ulli Diemer and Chris DeFreitas.

For information about being included in SOURCES as a expert or spokesperson see the FAQ or use the online membership form. Check here for information about becoming an affiliate. For partnerships, content and applications, and domain name opportunities contact us.