|

|

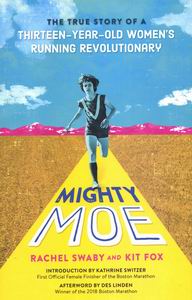

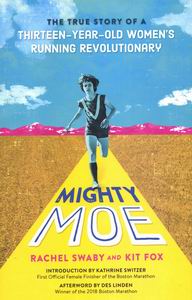

Mighty Moe:

The True Story of a Thirteen-Year-Old Women’s Running Revolutionary

By Rachel Swaby and Kit Fox

Publisher: Farrar Straus Giroux, New York, USA

Year Published: 2019 Pages: 300p Price: $26.99

Reviewed by Ulli Diemer

Mighty Moe tells the story of Maureen Wilton, a youthful long-distance runner from Toronto who set a women’s world record in the marathon in 1967, when she was 13. Wilton didn’t pursue an athletic career: a few years later, she stopped running and turned her life in a different direction: work, marriage, children. As the years passed, her accomplishments faded from memory until John Chipman tracked her down for a 2010 CBC radio documentary “Did My Mom Ever Run?” which gave Maureen, now Maureen Mancuso, another moment in the spotlight.

Authors Rachel Swaby and Kit Fox thought Maureen’s story was a story that should be known more widely. They told it first in a 2017 podcast for Runners World, and then in this book, which broadens the story to include the other young women who were Maureen’s teammates on the North York Track Club, as well as their coach, Sy Mah. The book is primarily aimed at readers aged 10 to 16, but readers of all ages will find it an enjoyable read.

Also woven into Maureen's story, as Swaby and Fox tell it, is Kathrine Switzer, who in April 1967 became the first woman to officially enter the Boston Marathon. She did it by registering as “K. Switzer” so race officials wouldn’t clue in to the fact that she was a woman. Once they found out, they tried to stop her from completing the race, but failed.

Sy Mah, the coach of the North York Track Club, had been waging a long and determined campaign to prove that girls and women could run long distances. When he heard about Switzer’s breakthrough, he invited her to come to Toronto to participate in the marathon that Maureen Wilton was entered in. Mah thought the presence of a second female runner in the race would be good for women’s participation in the sport, and would also take some of the pressure off Maureen. Switzer agreed, and ran, though, not fully recovered from Boston, she ended up finishing more than an hour behind Maureen.

Switzer, who has devoted her life to encouraging women’s participation in running, has written an introduction to Mighty Moe. She says “I’m reminded yet again how weird it is to have events from more than fifty years ago spiral back into your life.”

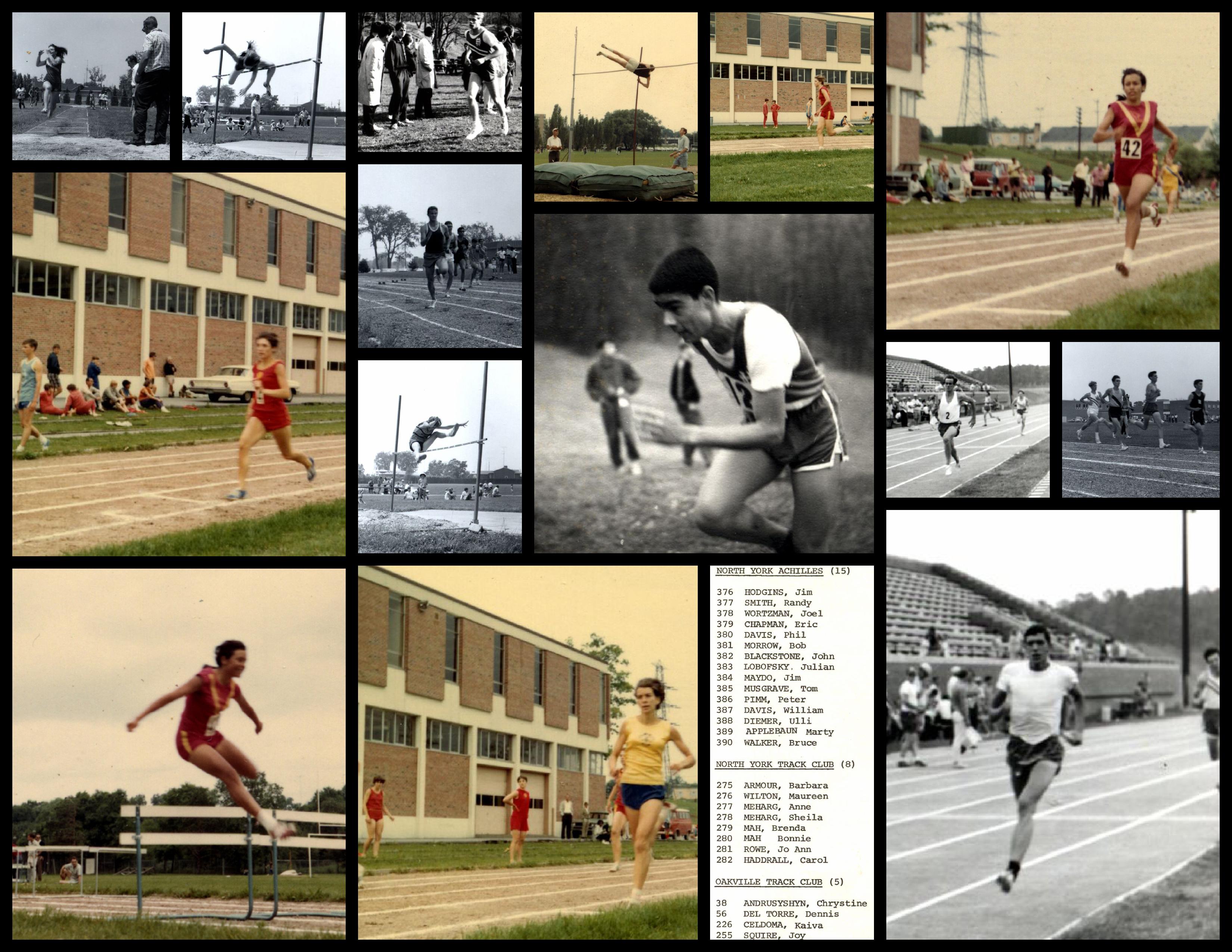

I had a similar feeling reading this book, which transported me back to the track and field world of the 1960s. I was a member of the North York Achilles Track Club in those days, running middle and long distances, though, unlike Maureen, I never endangered any records. The two clubs, North York and North York Achilles, drew most of their members from the same North York schools: Northview, Earl Haig, Downsview, Newtonbrook, Bathurst Heights (my school), and a couple of others. It was more or less automatic that if you were female, you went to the North York Track Club, and if you were male, you went to Achilles. At the time, I don’t think it ever occurred to me to wonder why this was so. Only in retrospect did it begin to dawn on me how important it must have been to young female athletes at the time to find a club with a coach like Sy Mah, who actually welcomed and encouraged girls and young women.

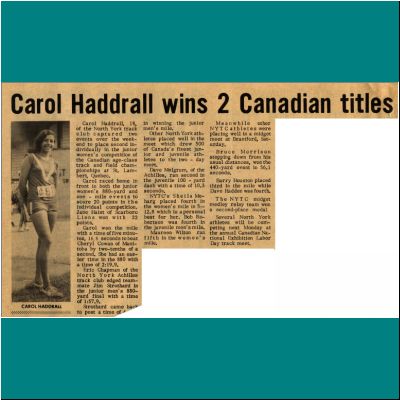

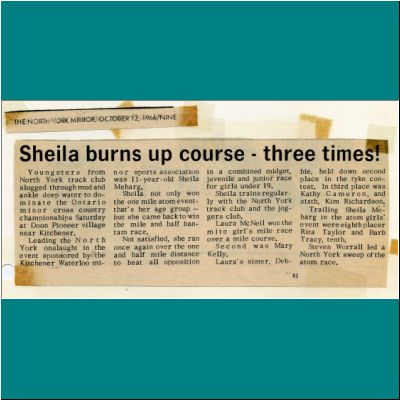

At the time, the prevailing wisdom was that girls and young women couldn’t, and shouldn’t, run long distances. Mah was having none of it. With his encouragement, his daughter Brenda started training at Earl Haig, where Mah was a physical education teacher and coach of the boys’ track team. In short order, Brenda Mah was making headlines in the North York Mirror, the local weekly newspaper, with her running accomplishments. As the word spread, other girls who wanted to run competitively, hearing of a club that would actually welcome them, headed to Earl Haig, where Sy Mah welcomed them into the newly formed North York Track Club. Maureen Wilton was one of them, as were Jo-Ann Rowe, Eva van Wouw, Sheila Meharg, and Carol Haddrall, a superb all-round athlete who was my classmate at Bathurst Heights. While Mighty Moe centres its attention on Maureen Wilton and her world record, these other young women are also given their due. As the authors say, “They are revolutionaries in their own right, each with a story worthy of its own book.”

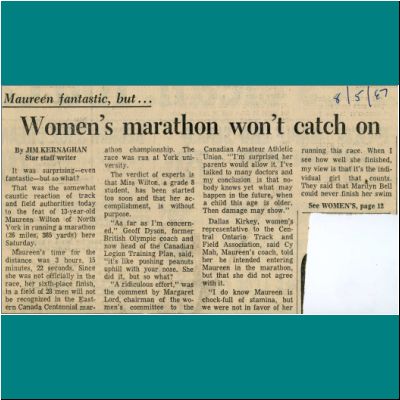

The sexism that athletes like Maureen Wilton faced erupted in all its unlovely petulance in the aftermath of her world record. The day before, the prevailing wisdom in Canada’s athletic establishment (mostly male, but including a few vocal women) was that women were incapable of running a race as long and grueling as a marathon. The ‘fragile female physique’ couldn’t handle it. It was impossible.

The day after Maureen Wilton not only ran the full 26.2 miles, but set a world record, suddenly the same voices were proclaiming that it was no big deal. A meaningless accomplishment, they said. “Nothing special.” “So what?” “Like pushing peanuts up a hill with your nose” were some of the comments from the establishment. What stands out is not merely the sexism of the time, but the visceral anger with which some male authority figures reacted to this mere girl who had gone ahead and done what they said couldn't be done.

I recall being shocked at the time by those reactions. It’s not that I was a full-fledged feminist in those days: I’m sure that if I were to go back and peer into my 1960s adolescent brain, I’d cringe at the sexist attitudes I’d find lodged there. But as a long-distance runner myself, I knew very well that it took a lot of physical and mental toughness to run a race like that, let alone set a record. If a male doing it merited praise, then a female did too: that seemed pretty clear.

I may also have been somewhat inoculated against the prevailing assumptions about what women should do, and what they couldn’t do, by the example of my own mother, who was raising me and my brother as a single mother working at a full-time job. My mother broke a few rules herself, so women flouting society’s expectations didn’t seem as shocking as it otherwise might have. (That preparation served me well, since as it happened women who were given to breaking rules were to loom large in my future.)

Mighty Moe relates the controversy that followed Maureen’s record-breaking run, controversy that understandably distressed her at the time. Nonetheless, it may be that the book goes too far in implying that those reactions are what led Maureen to walk away from competitive running a couple of years later. The story they tell suggests that the major turning point was actually Sy Mah’s departure from the North York Track Club a year-and-a-half later to take up a job in the U.S. He was replaced by a new coach who appeared not to like Maureen and constantly criticized her. Running stopped being fun, all the more so since most of Maureen’s closest friends left the club around the same time Mah did, depriving her of the comradeship of the teammates who had been her friends as well as rivals. In the end, it may simply have been that after six years of daily practices and weekend races, Maureen wanted to do something else with her life. There is a price to pay for becoming really good at one thing, and at a certain point the desire for a balanced life that doesn’t involve spending several hours a day on a track or in a gym causes most young athletes to decide to move on and seek to do something different. Life is a marathon, not a sprint. You’ve got to come up with a strategy that will take you the distance, and often you discover, after a while, that you aren’t even the same person who started out.

Swaby and Fox for their part are particularly focused on the negative reactions to Maureen’s world record, and they deplore the fact the Maureen didn’t get enough recognition for her accomplishments. With this book, they set out to rectify that injustice.

At the same time, it must be said that recognition has its downside. The authors don’t mention Elaine Tanner, whose story, which played out at the same time as Maureen Wilton’s, might have provided additional context for Maureen’s. Elaine Tanner – whose nickname “Mighty Mouse” was the inspiration for Maureen’s nickname “Mighty Moe” – was a swimmer who became a Canadian sports hero when she won four gold medals and three silvers at the 1966 Commonwealth Games in Jamaica. 15 years old at the time, she was the first person to win seven medals at the Commonwealth Games, and the first woman to win four golds. Later that year, she won the Lou Marsh Trophy, awarded to Canada’s top athlete – the youngest person ever to win the award, and one of the few women. The next summer – the same summer Maureen Wilton set her record – Tanner went on to win two gold and three silver medals in the Pan American Games, setting two world records in the process. The media and the public loved her.

And then came the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. Expectations were huge. Tanner won two individual silver medals, and a bronze in a relay, but the media were full of negative comments. Elaine Tanner had ‘only’ won three medals, and none of them were gold. She was a disappointment. (The entire 139-person Canadian team in Mexico won ‘only’ five medals in total, it should be noted.)

Elaine was crushed by the negative reaction. At age 18, she quit swimming and spiraled into depression and eventually homelessness. It took her years to get her life back. (She is now in a better space, and tells her story on her website www.elainetanner.ca)

The reaction to Maureen Wilton’s record-setting performance was by no means all negative. The most respected athletic coach in Canada, Lloyd Percival, sent her a personal letter of congratulations. The mayor of North York hosted a little ceremony to give her an award.

And more importantly, as Mighty Moe relates, her achievement changed attitudes and led to a breakthrough. The following year, 1968, the Toronto Police Games actively set out to invite women to participate in the marathon, and 15 signed up. Maureen’s teammate on the North York Track Club, Carol Haddrall, finished ahead of all the other women, including Maureen, thereby becoming the first official female finisher of any marathon in North America. From that point on, women were not merely tolerated, but encouraged to run marathons.

The future was less bright for the North York Track Club itself. Mah left for the job in the U.S. that fall, and, without his guiding vision and boundless energy, the club was never the same, eventually folding a few years later.

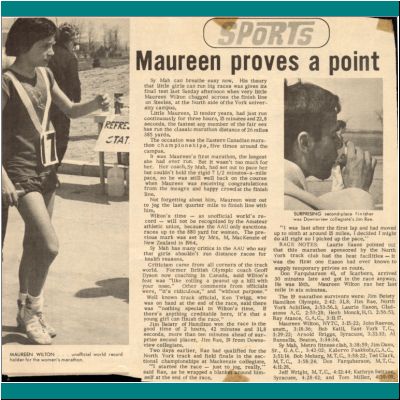

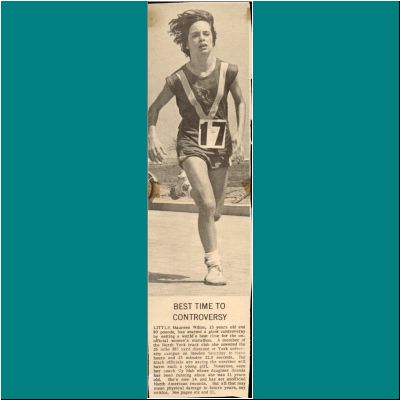

In addition to his coaching skills, Mah was also a dab hand at orchestrating publicity for his young athletes’ achievements. I remember from the time how frequently the North York Track Club appeared in the weekly North York Mirror, and sometimes in the Toronto Star as well. This was no accident, Swaby and Fox reveal. Mah saw it as part of his mission to alert the media to upcoming competitions in which his athletes would be participating, and to call them up after a track meet to tell them how they had fared. His efforts paid off in a rich harvest of publicity, one product of which was the scrapbooks that Maureen’s mother Margaret Wilton compiled. “This book,” Swaby and Fox say, “quite simply wouldn’t be possible without a collection of four scrapbooks, meticulously curated by Margaret Wilton over Maureen’s time as a runner.”

Such a scrapbook would not be possible now, because community newspapers like the North York Mirror, which came out weekly and were distributed free, door-to-door, have ceased to exist. Coverage of local news, including local amateur sport, has shrunk almost to the point of invisibility. Social media bubbles devoted to a particular activity are not at all the same, because the only people who know about them are those who are already in that bubble. One of the virtues of community newspapers like the North York Mirror was that they were so widely read by people who were interested in knowing what was going on in their community. They didn’t merely report: by the very fact of reporting, they helped to create and sustain community life, including local sports. (I used to be the editor of a community newspaper, so I may be a little biased on this topic.)

The sub-title of Mighty Moe is “The True Story of a Thirteen-Year-Old Women’s Running Revolutionary,” and one of the strong points of the book is its emphasis on the importance of what trailblazers like Maureen Wilton and her teammates accomplished. Their intentions weren’t revolutionary: they simply wanted to run and compete. But because there were those who didn’t think they should be allowed to do that, they had to fight battles off the track as well as on, and by fighting and winning those battles, they opened doors for many other girls and women who came after them.

It helped, too, that there were those within the world of physical education and athletics who rejected the prevailing orthodoxies of what girls and women should and shouldn’t do. Sy Mah was one: he didn’t believe the myth that girls would be hurt by running long distances, and set out to prove they could do it and excel. (His one failing in that regard was that he was also prone to shrug off injuries, advising his injured team members to keep going rather than take the time off they needed to recover.)

Those who clung to sexist stereotypes were women as well as men. Men predominated in the official sports bodies, so their voices were the loudest, but women like Margaret Lord, the chair of the Women’s Committee of the Canadian Amateur Athletic Union, were just as disapproving. “A ridiculous effort,” was Lord’s comment on Maureen Wilton’s marathon.

If Bathurst Heights was at all typical, phys ed teachers often seemed to be the loudest voices in opposing changes to women’s traditional roles. My partner Miriam, who went to Bathurst Heights a few years after me, described the battle girls had to wage in her time simply to be allowed to wear pants (important to Miriam because she wanted to ride her bike to school). When they eventually won that battle, her highly disapproving phys ed teacher told her that no girl who wore pants would ever be a ‘lady’ in her eyes. Since Miriam had no desire to be a lady, then or at any other time in her life, this did not impress her, but still, she was angered by the intended put-down. At the same time, the conclusion she drew was that if you want to win, you have to fight.

That ultimately is the story of Mighty Moe. Maureen Wilton and her teammates faced obstacles and criticism, but they battled on, they won, and they achieved a great deal. Running revolutionaries, as the authors call them. It’s a story worth telling, and Mighty Moe tells it well.

Ulli Diemer is a writer who lives in Toronto. His website is www.diemer.ca.

He can be reached at

Related:

Thinking about Terry Fox and the Marathon of Hope

Sports and politics

Returning to chess

Subject Headings:

Canadian Athletes –

Girls –

Track & Field –

Women –

Women in Sport

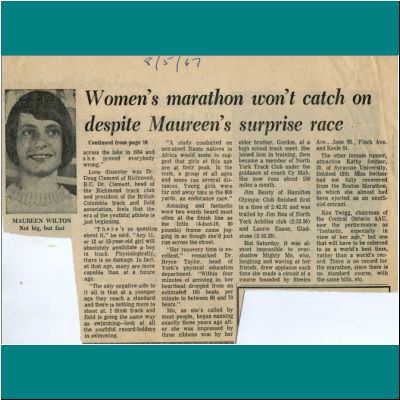

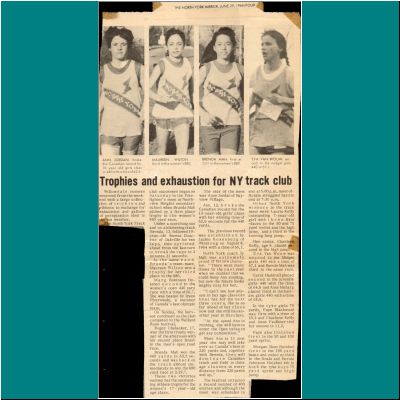

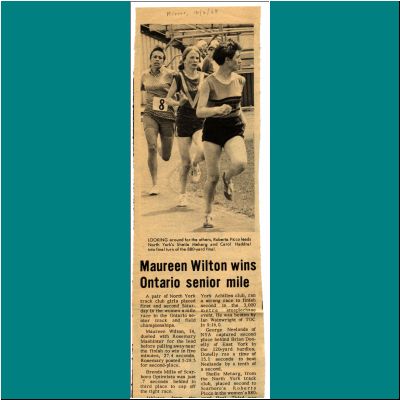

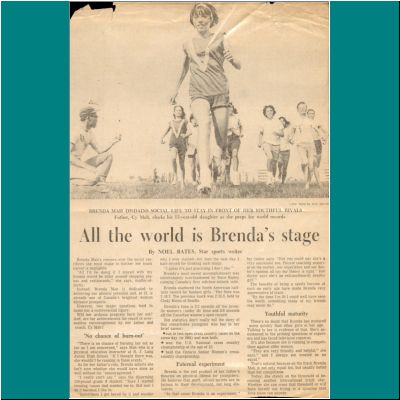

The accomplishments of Maureen Wilton and other members of the North York Track Club

were often highlighted in the newspaper. These clippings are from 1966 - 1968.

Click on an item to enlarge it.

|