| Home | Sources Directory | News Releases | Calendar | Articles | | Contact | |

Drang nach Osten

- "Drang nach Osten" is also a game in the "Europa" wargame series.

Drang nach Osten (German for "yearning for the East",[1] "thrust toward the East",[2] "push eastward",[3] "drive toward the East"[4] or "desire to push East"[5]) was a term coined in the 19th century to designate German expansion into Slavic lands.[4] The term became a motto of the German nationalist movement in the late nineteenth century.[6] In some historical discourses, "Drang nach Osten" combines historical German settlement in Eastern Europe, medieval military expeditions like the ones of the Teutonic Knights, and Germanisation policies and warfare of Modern Age German states like the Nazi lebensraum concept.[3][7] In Poland, the term ties in with nationalist discourse that put the Polish nation in the role of a suffering nation, particularly at the hands of the German enemy,[2] while on the German side the slogan was part of a wider nationalist discourse celebrating achievements like the medieval settlement in the east and the inherent idea of the superiority of German culture.[2] The slogan Drang nach Westen ("thrust toward the West") derived from "Drang nach Osten" was used to depict an alleged Polish drive westward.[2][8]

Contents |

[edit] Origin of the term

The first known use of "Drang nach Osten" was by the Polish journalist Julian Klaczko in 1849, yet it is debatable whether he invented the term as he used it in form of a citation.[9] Because the term is used almost exclusively in its German form in English, Polish, Russian, Czech and other languages, it has been concluded that the term is of German origin.[9]

[edit] Background

Drang nach Osten is connected with the medieval German Ostsiedlung. This "east colonization" referred to the expansion of German culture, language, states, and settlement into eastern European regions inhabited by Slavs and Balts.

Population growth during the High Middle Ages stimulated movement of peoples from the Rhenish, Flemish, and Saxon territories of the Holy Roman Empire eastwards into the less-populated Baltic region and Poland. These movements were supported by the German nobility, the Slavic kings and dukes, and the medieval Church. The majority of this settlement took place at the expense of Polabian Slavs and pagan Balts (see Northern Crusades).

The future state of Prussia, named for the conquered Old Prussians, had its roots largely in these movements. As the Middle Ages came to a close, the Teutonic Knights, who had been invited to northern Poland by Konrad of Masovia, had assimilated and forcibly converted much of the southern Baltic coastlands.

After the Partitions of Poland by the Kingdom of Prussia, Austria, and the Russian Empire in the late 18th century, Prussia gained much of western Poland. The Prussians, and later the Germans, engaged in a policy of Germanization in Polish territories. Russia and Sweden eventually conquered the lands taken by the Teutonic Knights in Estonia and Livonia.

[edit] "Drang nach Osten" in German discourse

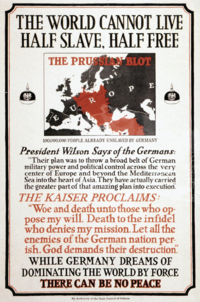

On the German side, the slogan was part of a wider national discourse celebrating achievements like the medieval settlement in the east and the inherent idea of the superiority of German culture.[2] The term became a centerpiece of the program of the German nationalist movement in 1891, with the founding of the Alldeutschen Verbandes, in the words: –žDer alte Drang nach dem Osten soll wiederbelebt werden" ("The old Drang nach Osten must be revived")[10]. Nazi Germany employed the slogan in calling the Czechs a "Slav bulwark against the Drang nach Osten" in the 1938 Sudeten crisis.[4]

Despite Drang nach Osten policies, population movement took place in the opposite direction also, as people from rural low-developed areas in the East were attracted by the prospering industrial areas of Western Germany. This phenomenon became known by the German term Ostflucht, literally the flight from the East.

[edit] "Drang nach Osten" in Polish and Panslavic discourse

According to Henry Cord Meyer, in his book "Drang nach Osten: Fortunes of a Slogan-Concept in German-Slavic Relations, 1849-1990" the slogan "Drang nach Osten"[11] most likely originated in the Slavic world, where it also was more widely used than in Germany: "its main area of circulation has been the Slavic world. Indeed, most German scholars have rejected the slogan as mere Panslav (or later, Soviet) agitation against Germany." It was "a mainstay in Soviet bloc historiography--and propaganda. [...] Even if the concept has found broad acceptance in Slavic historiography since World War II, this does not mean that it is factually accurate. The phrase is most often used to suggest a basic continuity in German history from the eleventh century to the present; it is closely linked to Slavic stereotypes of the German national character."[11]

With the development of romantic nationalism in the 19th century, Polish and Russian intellectuals began referring to the German Ostsiedlung as Drang nach Osten. The German Empire and Austria-Hungary attempted to expand their power eastward; Germany by gaining influence in the declining Ottoman Empire (the Eastern Question) and Austria-Hungary through the acquisition of territory in the Balkans (such as Bosnia and Herzegovina).

In Poland, the slogan was in use since the mid-19th century, and since then was used to suggest a continuous historical trend since 1000 AD, referring back to practices of the Teutonic Knights and medieval Ostsiedlung and thereby coupling geopolitical projects with an alleged national character and an "organic unity" of the German nation.[2] The slogan ties in with national discourse that put the Polish nation in the role of a suffering nation, particularly at the hands of the German enemy.[2] Alongside the Kulturkampf policies directed against Catholics, Imperial Germany tried to colonize its eastern (mostly-Catholic) Polish-inhabitated territories with Germans, to which "Drang nach Osten" was also applied.[2]. A contemporary Polish encyclopedia defined the slogan in 1896 as "the drive of the Germans eastward in order to de-nationalise the Polish people".[2] The term also tied in with Pan-Slavist ideas.[2]

[edit] Drang nach Westen

A new Drang nach Osten was called for by German nationalists to oppose a Polish Drang nach Westen ("thrust toward the West").[2][8] World War I had ended with the Treaty of Versailles, by which most or parts of the Imperial German provinces of Posen, West Prussia, and Upper Silesia were given to reconstituted Poland; the West Prussian city of Danzig became the Free City of Danzig. The Polish paper Wprost used both "Drang nach Osten" and "Drang nach Westen" in August 2002 to title stories about German RWE company taking over Polish STOEN and Polish migration into eastern Germany, respectively.[12]

"Drang nach Westen" is also the ironic title of a chapter in Eric Joseph Goldberg's book Struggle for Empire, used to point out the "missing" eastward ambitions of Louis the German who instead expanded his kingdom to the West.[13]

[edit] Lebensraum concept of Nazi Germany

Adolf Hitler, dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933-1945, called for a Drang nach Osten to acquire territory for German colonists at the expense of eastern European nations (Lebensraum). The term by then had gained enough currency to appear in foreign newspapers without explanation.[14] His eastern campaigns during World War II were initially successful with the conquests of Poland and much of European Russia by the Wehrmacht; Generalplan Ost was designed to eliminate the native Slavic peoples from these lands and replace them with Germans. As for settlements actually established during the war, the settlers were not colonists from the Altreich, but in the main part East European Germans resettled from Soviet "spheres of interest" according to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. However, the Soviet Union began to reverse the German conquests by 1943, and Nazi Germany was defeated by the Allies in 1945.

[edit] Expulsion of Germans from the East after World War II

Most of the demographic and cultural outcome of the Ostsiedlung was terminated after World War II. The massive expulsion of German populations east of the Oder-Neisse line in 1945-48 on the basis of decisions of the Potsdam Conference were later justified by their beneficiaries as a rollback of the Drang nach Osten. Historical Eastern Germany was split between Poland, Russia, and Lithuania and repopulated with settlers of the respective ethnicity. The Oder-Neisse line has been gradually accepted to be the eastern German boundary by all post-war German states (East and West Germany as well as reunited Germany), dropping all plans of (re-)expansion into or (re-)settlement of territories beyond this line.

[edit] References

- Inline

- ^ Pim den Boer, Peter Bugge, Ole Wæver, Kevin Wilson, W. J. van der Dussen, Ole Waever, European Association of Distance Teaching Universities, The history of the idea of Europe, 1995, p.93, ISBN 0415124158, 9780415124157

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ulrich Best, Transgression as a Rule: German-Polish cross-border cooperation, border discouse and EU-enlargement, 2008, p.58, ISBN 3825806545, 9783825806545

- ^ a b Jerzy Jan Lerski, Piotr Wróbel, Richard J. Kozicki, Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945, 1996, p.118, ISBN 0313260079, 9780313260070

- ^ a b c Edmund Jan Osmańczyk, Anthony Mango, Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements, 2003, p.579, ISBN 0415939216, 9780415939218

- ^ Marcin Zaborowski, Germany, Poland and Europe, p.32

- ^ W. Wippermann, Der "deutsche Drang nach Osten": Ideologie und Wirklichkeit eines politischen Schlagwortes, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1981, p. 87

- ^ Ingo Haar, Historiker im Nationalsozialismus, p.17

- ^ a b Bascom Barry Hayes, Bismarck and Mitteleuropa, 1994, p.17, ISBN 0838635121, 9780838635124

- ^ a b Andreas Lawaty, Hubert Or�owski, Deutsche und Polen: Geschichte, Kultur, Politik, 2003, p.34, ISBN 3406494366, 9783406494369

- ^ Wippermann, 1981, S. 87

- ^ a b Hnet Revier of Henry Cord Meyer. Drang nach Osten: Fortunes of a Slogan-Concept in German-Slavic Relations, 1849-1990. Bern: Peter Lang, 1996. 142 pp. Notes and index. $29.95 (paper), ISBN 978-3-906755-93-9. Reviewed by Douglas Selvage , Yale University.

- ^ Paul Reuber, Anke Strüver, Günter Wolkersdorfer, Politische Geographien Europas - Annäherungen an ein umstrittenes Konstrukt: Annäherungen an ein umstrittenes Konstrukt, 2005, ISBN 3825865231, 9783825865238

- ^ Eric Joseph Goldberg, Struggle for Empire: Kingship and Conflict Under Louis the German, 817-876, p.233ff, 2006, ISBN 080143890X, 9780801438905

- ^ Carlson, 233.

- General

- Carlson, Harold G.; John Richie Schultz (October 1937). "Loan-Words from German". American Speech (American Speech, Vol. 12, No. 3) 12 (3): 232'234. doi:10.2307/452436. http://jstor.org/stable/452436.

[edit] See also

|

SOURCES.COM is an online portal and directory for journalists, news media, researchers and anyone seeking experts, spokespersons, and reliable information resources. Use SOURCES.COM to find experts, media contacts, news releases, background information, scientists, officials, speakers, newsmakers, spokespeople, talk show guests, story ideas, research studies, databases, universities, associations and NGOs, businesses, government spokespeople. Indexing and search applications by Ulli Diemer and Chris DeFreitas.

For information about being included in SOURCES as a expert or spokesperson see the FAQ or use the online membership form. Check here for information about becoming an affiliate. For partnerships, content and applications, and domain name opportunities contact us.